Appendix B — Interview materials

Various materials were used to recruit participants and record structured data both for the research, and recording matters like consent, while the interviews were arranged and conducted. Copies of all these materials are included below.

B.1 Participant information sheet

Project:

Ethical self-governance among men serving life sentences for murder

Researcher:

Ben Jarman

Who am I?

I am a researcher at the University of Cambridge. Before this, for several years, I worked for various charities in different prisons around England and Wales.

Why am I doing this research?

In my previous jobs, I became interested by what people told me about their lives in prison, and their feelings about punishment and rehabilitation. I want to find out more about how people feel they change when they’re in prison for a long time: how change gets started, what keeps it going, and what gets in the way.

What will participation involve?

If you send back the slip on the back of this booklet and tell me you might be interested, I’ll approach you for an initial conversation. Mostly this will cover practical stuff like when would be the best times for you to meet for a full interview. If you are currently appealing your sentence or conviction, or if you are maintaining innocence, I will also need to know that.

If you agree to be involved, I will interview you, asking you to talk about your life before prison and your life in prison. The interview will be in two parts. The length of each part will vary depending on how much you want to say. Expect each half to take at least an hour – I will arrange it so that you are off work for the morning or afternoon where the interview takes place unless you prefer some other arrangement. You can take breaks if you want to, for any reason. I want to give you time to say what you need to say, and I will make sure the interview fits around your needs.

After all my interviews are done, at the end of my time in the prison, I would also like to look at some of the prison’s records about you. If you give me permission, I will read the relevant records, and note down a summary of your index offence, conviction history, disciplinary record in prison, and courses you have done. I won’t do this before I interview you, and you will be in control: if you don’t give your permission, I won’t ask the prison to show me your records.

Do you have to take part?

No. Your participation is voluntary. If you don’t want to be involved, you don’t have to be. This will not cause you any disadvantage.

Are there any risks involved in taking part?

I will ask you to talk about various aspects of your life before prison and in prison. It is possible that some questions might cover things you don’t think about often, or you generally prefer not to think about. Some questions might trigger unhappy or upsetting thoughts, though this is unlikely.

My priority is to avoid the interview causing you any harm. You can decide not to answer any particular question if you prefer not to. You can also take a break or stop completely, at any time. This won’t count against you. There will be time at the end to discuss anything you have found difficult. If you like, you can also tell me the name of a Listener, a chaplain, a mentor, a staff member, or someone else that you trust. If you found the interview difficult and you want to talk more about it with someone else afterwards, I can approach them for you, and ask them to check in with you.

Are there any benefits to taking part?

I am not allowed to pay you to take part. But the prison has agreed you will not lose pay, if taking part means you miss work or education. Taking part will have no effect on your IEP, categorisation, or parole.

Sometimes, prisoners my colleagues and I have interviewed say they get something positive from the experience. They welcome the chance to speak about their lives to someone from outside who is interested and wants to listen. For our part, we appreciate the chance to hear about prison life from your point of view.

Will what you say be confidential?

I do not work for the Prison Service, and my work is funded by independent organisations. When based in the prison, I will be using desk space there, but I have no formal role, and my papers and equipment are either carried around with me or taken out of the prison at the end of every day.

I take great care with the information you share with me, and what you say to me is confidential: no one else will see it, hear it, or read it. But there are three exceptions. If what you tell me is about any of the following, I am obliged to tell the prison:

- behaviour that is against prison rules and can be adjudicated against

- undisclosed illegal acts

- behaviour that is potentially harmful to you or others (e.g. intentions to self-harm or complete suicide)

Everything else is confidential.

Will your contribution remain anonymous?

If you are interviewed, you don’t have to agree to be quoted. You also don’t have to agree to let me record the interview; if you prefer, I will just write notes.

If you agree to let me record the interview, the recording will be stored securely and destroyed as soon as I’ve turned it into a written transcript (see below for more info). In the transcript, you will have a different name, and I will change or leave out any details (such as places or the names of other people) which could give away who you are. Nothing I write will allow you to be identified or linked back to anything you say.

How do you agree to take part?

If you would like to take part, please detach and return the reply slip (page 7 of this booklet), either by handing it to me, or sending it via the prison’s internal post. Address it to me (Ben Jarman) c/o [name of staff member], and she will pass it on to me.

If you agree, I’ll contact you to arrange an interview. We’ll start by going over some things on this sheet again in person, and then I’ll ask you to confirm your consent in writing.

How will information be retained, why, and for how long?

I will keep what you tell me for the following reasons and the following period of time, as follows:

| What | Why | How long |

|---|---|---|

| Interview recordings or interview notes (depending on whether you let me record) | To make an anonymous transcript | Until the transcript is finished, or 1 year after the date of the interview (whichever is earlier) |

| Anonymised interview transcripts (or notes) | To write up the research If I do follow-up research, to remind me what you said before |

Up to ten years after the project is finished, or October 2032 (whichever is earlier) |

| Other identifying details (e.g. your name, prison number or date of birth) | To find you if I decide to do follow-up research | Up to ten years after the project is finished, or October 2032 (whichever is earlier) |

| Notes on your prison records (if you let me view them) | To compare what prison records say about you with what you say about yourself | My notes: until an anonymised summary is finished, or 1 year after the date of the interview (whichever is earlier) Anonymised summary: Up to ten years after the project is complete, or October 2032 (whichever is earlier) |

All information will be stored securely. The only person able to view it will be me.

What if you want to withdraw from the study?

You can stop an interview at any time without giving a reason. If you were interviewed but change your mind later about taking part, you can also remove yourself from the study. This will not disadvantage you in any way. You can do this at any point up until 30th June 2020. If you do, I will destroy all records I have relating to you.

If you want me to do this, you should write to me using the address on page 4.

What will happen to the results of the study?

The results of the study will be written up as a long piece of writing, and shorter versions might also be published in places like academic journals and on my project website. Published information of any kind will be written so that it will be impossible to identify you or link you personally to the research.

I might decide to talk about the results with Prison Service staff, or with other researchers. This could happen face-to-face at conferences, training sessions and so on. If I do this, I’ll be talking about the overall findings, not about you personally, and you won’t be identifiable in any quotes I might use.

I might decide to contact you in the more distant future, to interview you again and find out how you are doing some years after the initial interview. If I do this, I will read your original interview again to remind myself about what you said before.

What if you want more information, or you want to make a complaint?

Further information about the study can be obtained by writing to me or my academic supervisor, Ben Crewe, at the address below.

If you would like a copy of the research when it is finished, please write to me to ask for one.

The plans for the study have been reviewed by HM Prison & Probation Service, and by the Ethics Committee in my university. If you want further information about this, or if you want to complain about me or any aspect of the research, you should write to Professor Crewe.

Addresses

To say you no longer want to participate, or to ask for a copy of the finished work: Ben Jarman Prisons Research Centre Institute of Criminology Sidgwick Avenue Cambridge CB3 9DA |

To ask about the ethical approval for the study, or to complain about me or the research: Professor Ben Crewe Prisons Research Centre Institute of Criminology Sidgwick Avenue Cambridge CB3 9DA |

Thank you for reading this. If you want to ask anything else, you can tick the appropriate box on page 7

Appendix: How the University uses your personal information

1. Why have I been given this extra sheet?

This document supplements the specific information you have already been given (on pages 1-4 above) in connection with your participation in a research study or project run by academic researchers at the University of Cambridge. The information below—which we are obliged to supply you with—applies to all studies and projects that we run. If there is any contradiction between this general information and the specific information you have already been given, the specific information takes precedence.

2. Who will process my personal information?

The information published here applies to the use of your personal information by the University of Cambridge, including its Departments, Institutes and Research Centres/Units.

You have already been told about the types of personal information we will use in connection with the specific research study or project you are participating in and (where applicable) its sources, any data sharing or international transfer arrangements, and any automated decision-making that affects you.

3. What is the purpose and legal basis of the processing?

In general terms, we use your personal information (including, where appropriate, sensitive personal information) to carry out academic research in the public interest.

Please note that your consent to use your personal information is separate from your ethical consent to participate in a particular research study (which we usually request for relevant types of research).

You are not legally or contractually obliged to supply us with your personal information for research purposes.

4. How can I access my personal information?

Various rights under data protection legislation, including the right to access personal information that is held about you, are qualified or do not apply when personal information is processed solely in a research or archival context. This is because fulfilling them might adversely affect the integrity of, and the public benefits arising from, the research study or project.

The full list of (qualified or inapplicable) rights is: the right to access the personal information that is held about you by the University, the right to ask us to correct any inaccurate personal information we hold about you, to delete personal information, or otherwise restrict our processing, or to object to processing (including the receipt of direct marketing) or to receive an electronic copy of the personal information you provided to us.

If you have any questions regarding your rights in this context, please use the contact details below.

5. How long is my information kept?

You have already been told about the long-term use (and, where applicable, re-use) and retention of your personal information in connection with the specific research study or project you are participating in.

6. Who can I contact?

If you have any questions about the particular research study you are participating in, please use any contact details you have already been supplied with.

If you have any general questions about how your personal information is used by the University, or wish to exercise any of your rights, please write to the Data Protection Officer, c/o Information Compliance Office, Registrar’s Office, University of Cambridge, The Old Schools, Trinity Lane, Cambridge, CB2 1TN.

7. How do I complain?

If you are not happy with the way your information is being handled, or with the response received from us, you have the right to lodge a complaint with the Information Commissioner’s Office at Wycliffe House, Water Lane, Wilmslow, SK9 5AF.

This text was last updated in May 2019.

B.2 Interview appointment memo

To:

Location:

From: Ben Jarman

Date:

Re: Research interview

Dear

Thanks for agreeing to participate in a research interview with me.

I’ve booked the interview as an appointment so that you won’t lose any pay for whatever else you would have been doing at this time. The interview will take place as follows:

Date:

Time:

Location:

If you wear glasses, it might be useful to bring them with you (but it’s not essential).

Other than this you don’t need to bring anything – just yourself!

See you then,

B.3 Consent form

Project title: Ethical self-governance among men serving life sentences for murder

Researcher: Ben Jarman

Please CIRCLE the answers to indicate whether you AGREE with the following statements.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please tick one box to answer YES or NO to the following statements.

|

|

|

|

|

Please add your name, the date, and signature.

Name of Participant: Date: Signature: |

Name of Researcher: BEN JARMAN Date: Signature: |

To be completed by the researcher: Personal identifier: Participant’s research code: |

|

B.4 Participant demography sheet

Project title: Ethical self-governance among men serving life sentences for murder

Researcher: Ben Jarman

About you and your sentence

| Name and NOMS number | |

| Participant ID (to be completed by the researcher) | |

| What is your gender? | |

| What is your date of birth? | |

| What date were you sentenced? | |

| When does your tariff expire? | |

Is this your first prison sentence? (if ‘No’, please tick how many prison sentences you have had before) |

|

| How old were you when you were first convicted of any crime? | ____ years old |

| When did you come to to this particular prison? | |

| I consider myself guilty of the offence of which I was convicted |

About you and your life before prison

| Ethnicity | Asian/Asian British | |

| Black/Black British | ||

| Mixed | ||

| Other | ||

| White | ||

| Not stated | ||

| Religion | ||

| What is the highest level of education you completed before entering prison? | ||

| What is your marital status? | ||

Do you have children? (if ‘yes’, please indicate what kind of custody you had of them before prison) |

||

B.5 Prison timelines

The second (prison history) interview commenced by asking participants to use an A3 sheet marked with a set of ‘axes’, to give a narrative overview of the sentence to date. This was used because the interviews would be participants who had served vastly different periods of time in prison, meaning that a purely narrative interview would not be a good use of time; but I did not want the interview to be purely thematic, and instead sought some means of giving myself an overview of the ‘story’ of the sentence, and to sensitise myself to issues that might be interesting to probe further, for example periods in notoriously bad prisons, or in intensive risk-reducing interventions such as high-intensity therapeutic units.

The template (Figure B.1), as well as soliciting a chronological account of participants’ prison trajectories, also asked them to link the experiences they were describing to descriptions of whether they were ‘feeling good’ (marked by drawing a line higher up the page), or ‘feeling bad’ (marked lower down the page). In introducing the exercise at the start of the interview I always drew three examples on the back of the paper to demonstrate the idea, narrating hypothetical examples based on syntheses of other participants’ sentence narratives.

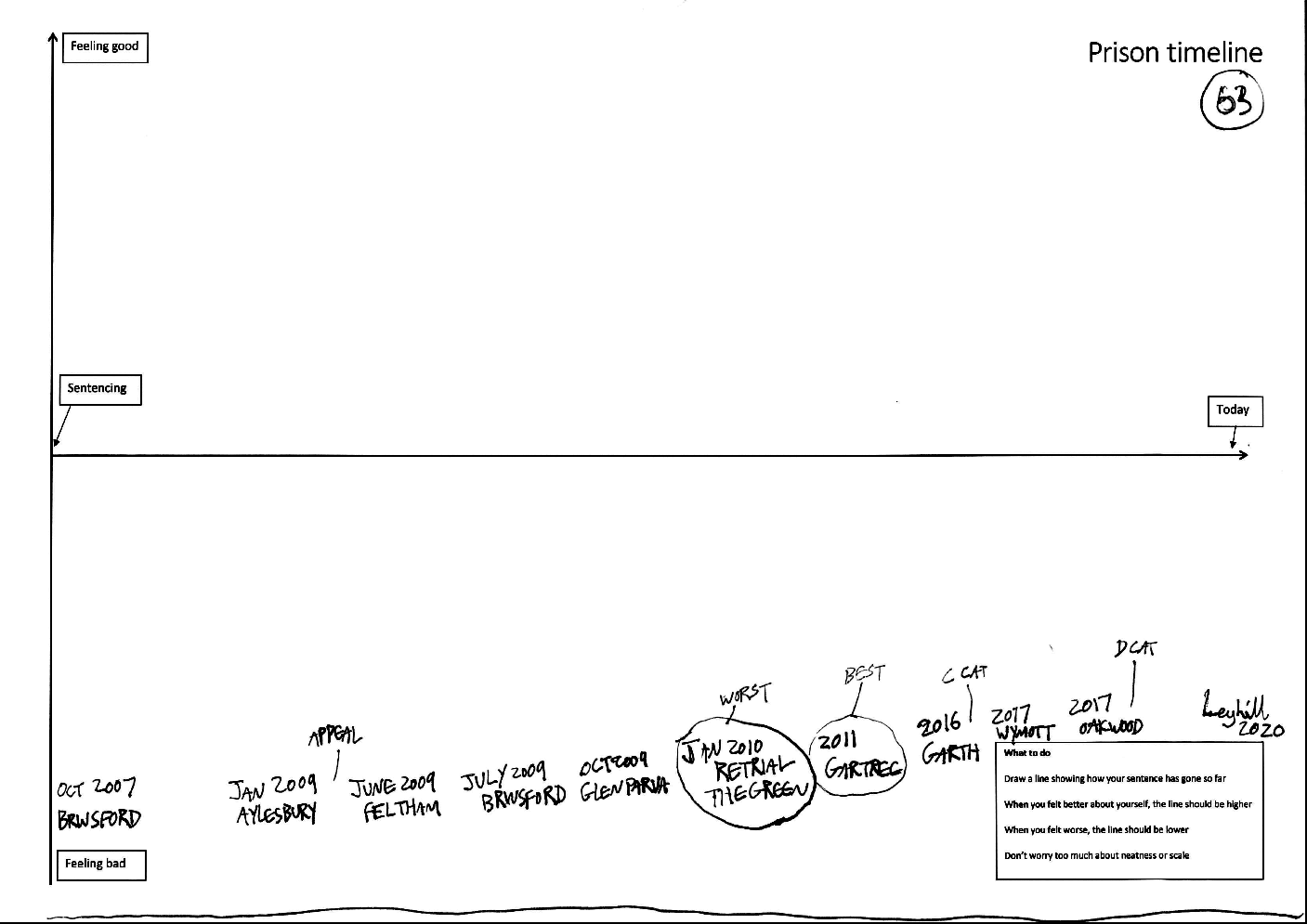

The timeline was used very differently by different prisoners. In some cases, it was completed in a matter of seconds, and the idea of marking times that ‘felt bad’ or ‘felt good’ was rejected or ignored, as though ridiculous. Figure B.2 shows one such example; here, the participant said that all prison experiences were bad experiences, and simply listed (verbally and in writing) the prisons where he had served his time. In cases such as these, it was as though the participant was resisting the idea that prison time could be meaningful at all, although not all of these ‘minimalist’ timelines described universally negative experiences: a couple of men, including one who was in the Late stage of the sentence, completed the page similarly quickly and said that they had found the sentence consistently easy, interesting, or even “enjoyable”.

In most cases, however, the participants took to the exercise readily, immediately grasping the notion that one’s experiences fluctuated in prison, and could be narrated to imbue them with biographical meaning. Figure B.3 is the most ‘maximal’ of these; the author, a post-tariff man in his fifties at Swaleside who was the first man in the entire PhD who I did the second interview with, spent two and a half hours drawing the line a centimetre or so at a time, and then annotating and explaining it in depth, interspersed with my questions. By the end of this we had barely any time left for the interview schedule, though we had also covered nearly all the topics I had been intending to ask about.

The exercise demonstrated something useful to me, which was that some prisoners were far readier to narrate prison time as meaningful, whereas others were specifically resistant to doing so. Tellingly, nearly all the men who did not want to describe meaningful ‘ups and downs’ were also those who maintained innocence to some degree. This recalls the finding of Grounds (2005) that imprisonment experienced as wrongful imposes a highly consequential rupture in biographical meaning.

B.6 Interview schedule

Checklist of formalities

Check participant has had the information sheet

Ask if they have any questions or if there was anything they didn’t understand

Underline the issue of confidentiality and explain what I have to disclose:

Ask whether they are happy:

If so, get them to complete and sign the consent form

Explain that I have to enter something in NOMIS to say the interview has taken place but won’t say what was said

Begin the interview

Life history segment

Aims of this section:

- a way into the interview

- a way to build rapport

- trying to establish a picture of the background to the offence

- probing as to ethical life and worldview before prison

| Question | Prompt/possible follow-on questions | Be alert to/probe further for… | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | OK, so later in the interview I’m going to ask you about how you came to be in prison, but I want to make sure that I put everything in its proper context, make sure I understand where you’re coming from. So could you start by telling me about your early life – your family, where you grew up, that kind of thing? |

|

|

| 2 | When you were a young man, what did a ‘good life’ look like to you then? |

|

|

| 3 | Did you have any kind of involvement in crime or with the criminal justice system before the events that led to you being in prison now? |

|

|

| 4 | If a stranger were to ask you to describe yourself at the time of your index offence, what would you say? |

|

|

| 5 | Do you mind me asking about the events that led to you being in prison now? I know this might be a difficult topic, so thank you for being willing to talk about it. Just start where you think you need to start. I’m interested in how you see things, so just focus on describing how things happened, and start where you think you need to start. If I have any questions, or there’s something I don’t understand, I’ll ask – but you don’t have to answer, and if you prefer me to shut up and listen, I’ll do that. |

|

|

| 6 | What do you remember about the trial? |

|

|

| 7 | Looking back, what are you proud of from your life before prison? |

|

|

Warm-down questions

| Question | |

|---|---|

| 7a | What made you decide to come along here for this interview today? |

| 7b | Is there anything you want to say anything else about? |

| 7c | What’s it been like talking about all of this today? Is there anything you’ve found it difficult to talk about? |

| 7d | Is there anyone you would like me to tell so you can get some support with that? |

Prison history segment

This section of the interview aims to gather data towards the research questions, as follows:

- How are men’s personal ethics affected by being imprisoned for murder?

- How do they respond to moral messages they receive, via conviction and punishment, about the offence of murder and their own conduct?

- What ‘ground projects’ and ethical priorities do they adopt as the sentence proceeds?

- How do their personal ethical priorities interact with the demand to self-govern and 'reduce risk'?

- What are their experiences of hope and meaning, and how do these alter the experience of punishment?

| Question | Prompt/possible follow-on questions | Be alert to/probe further for… | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | What have been the key moments in the sentence so far? (use a timeline template to structure the response to this question) |

|

|

| 9 | What have been the moments when you’ve felt like you were making progress? |

|

|

| 10 | What’s your main daytime activity at the moment? |

|

|

| 11 | Are you involved in any religious or spiritual activities in the prison? |

|

|

| 12 | When you’re not at work/education/[whatever], how do you pass your time? |

|

|

| 13 | Have you been in trouble with the prison authorities since you were sentenced? |

|

|

| 14 | Looking back to the start of the sentence, did you expect any good to come of it? |

|

|

| 15 | You talked last time about what the judge said at your trial. Did those words spoken in the sentencing hearing matter to you at the time? |

|

|

| 16 | How comfortable do you feel now about describing yourself as ‘a good person’ before you came to prison? |

|

|

| 17 | In difficult moments, has it been possible to have honest conversations with other people about what you’re finding difficult? |

|

|

| 18 | Have you been able to have honest conversations to help you work through your feelings about your offence? |

|

|

| 19 | Has there ever been a time when someone said or did something that made you feel bad about your offence? |

|

|

| 20 | Do people in here make moral judgments about the kind of offence you were convicted of? |

|

|

| 21 | Are those kinds of beliefs consistent among different people you encounter in prison? |

|

|

| 22 | What’s the most meaningful thing in your life now, as far as you are concerned? |

|

|

| 23 | What does it mean to you right now to be a good person or to live a good life? |

|

|

| 24 | Would you say you have changed since you’ve been in prison? |

|

|

| 25 | Do you have any regular practices, routines or habits that are important to you? |

|

|

| 26 | As far as you know, do you have a sentence plan at the moment? What’s on it? |

|

|

| 27 | You’ve has some experience of [making progress]/[being recategorised]. What was it like, working towards that point? |

|

|

| 28 | Have you done any offending behaviour courses? |

|

|

| 29 | Have you ever had any doubts about courses? |

|

|

| 30 | How do you think about the time you’ve got left in prison now? |

|

|

| 31 | Where do you see yourself a year after the end of your tariff? |

|

|

| 32 | Have there been people in prison who you have looked up to or admired in any way? |

|

|

| 33 | What about you - as far as you know, what characteristics do others in here admire or look up to in you? |

|

|

| 34 | Would you say that you have gained anything that matters to you during your time in prison? |

|

Warm-down questions

| Question | |

|---|---|

| 35a | What’s it been like talking about everything we have talked about today? Did you find anything difficult to talk about? |

| 35b | Is there anyone you would like me to tell so you can get some support with that? |

| 35c | Thinking about the things we’ve talked about, are there any questions I should be asking, but I haven’t? |

| 35d | Is there anything you want to say anything else about? |