6 Risk and self-governance

Moral communication through offender management

The ‘ruling concept’ through which English prisons communicate with prisoners about the moral obligations associated with their punishment is risk. Risk thinking and risk talk pervade the management of lifers and prisoners generally, and the management of risk is a primary conduit for the operation of power. This has been said to produce distinctively ‘tight’ prison pain, for those governed through risk. This chapter reviews how risk factored in the sample’s ethical lives: how they made sense of the concept, or in some cases, dismissed it as a bad-faith imposition. In doing so, it summarises official documents to describe the risks associated with the sample by risk assessments, which broadly suggested that the participants were ordinary and ‘easy-keeping’ lifers: compliant, mostly self-governing, adapted to imprisonment, and posing few risks to others in custody. This, the chapter argues, means they were subject to discontinous, and varying, kinds of ‘grip’, with ‘tight’ conditions prevailing for some, but ‘loose’ and ‘lax’ treatment for others. The analysis points to variations in how far the sample were conscious of these variable and inconsistent expectations, and shows that some felt their ‘lax’ treatment to be ‘neglectful’. It produces a typology of ethical responses to moral communication about risk, and, in a closing discussion, suggests what an ethical approach adds to our understanding of risk governance.

life imprisonment, looseness, moral communication, murder, penal theory, punishment, risk, risk governance, subjectivation, tightness, offender management

Increasingly, prisoners are no longer objects of punishment, but made instead into potential subjects of self-change, thus creating prisons characterized by what Crewe has called ‘neo-paternalism’. The feeling of ‘tightness’ [is] connected to the perceived need to self-govern, take responsibility and show credible change and growth.

Ugelvik and Damsa (2018 p. 1028), referencing Crewe (2009, 2011a)

Punishment enforces twin obligations, backing each with the threat of coercion. One is retrospective: to confront culpability. The other is reformative: to take responsibility for future conduct. They are not entirely separable, but whereas Chapters 4 and 5 examined participants’ approach to the first obligation, this chapter focuses more squarely on the second: their attitudes to official attempts to induce self-governance, largely through the medium of ‘risk’, the central organising concept in the prison’s moral communication.

The finding that risk governance is entangling and painful, particularly for indeterminately-sentenced prisoners, is perhaps most associated with the work of Ben Crewe (2011a). In this sample, however, the pains of being tightly ‘harnessed’ by the prison were not uniformly evident. This was partly because risk-related expectations—the content of moral communication—differed between the two sites. It was also because moral messages were heard differently, too: some participants saw risk-reducing intervention as a legitimate attempt to offer them needed help, while others found it illegitimate and oppressive, resenting interference in their attempts to prepare for future life.

This chapter explores the contrast, by four steps. First, I set out key concepts used in the empirical analysis. Second, I sketch a descriptive ‘risk profile’ for the sample. Third, I describe the characteristic styles of moral communication evident at Swaleside and Leyhill, and exemplify the guidance (if any) they offered on risk. I characterise Swaleside as generally ‘loose’ and ‘neglectful’ (albeit with pockets of ‘laxity’ and ‘tightness’); and Leyhill as extremely ‘tight’, unexpectedly so for many participants. Finally, I develop this into an analysis of adaptation styles, identifying four ‘ethical responses’ to risk governance evident in the sample. A closing discussion suggests that whether prisoners find risk governance painful or not may often be a consequence of imported factors in their personal history, including the offence. This finding adds nuance to existing accounts, which tend not to differentiate systematically between how prisoners with distinct characteristics respond to risk-based forms of rehabilitative intervention.

6.1 Conceptualising experiences of risk intervention

The empirical analysis in this chapter borrows conceptual terminology from two main sources. Table 6.1 summarises them.

One is Ben Crewe’s influential ‘tightness’ framework (see, variously, 2011a, 2015; 2021). It suggests that indeterminate sentences are distinctively punitive because they entangle prisoners in risk-management structures, which demand compliance and self-governance, but are also hard to understand and comply with. The conceptualisation has recently been revised to reflect new findings (Crewe and Ievins 2021; Ievins and Mjåland 2021): relating, first, to the differing demands made by different penal regimes, and the varied support offered to help prisoners meet these demands; and, second, to the observation that not all intervention is unwelcome. Often, Crewe and Ievins (2021 p. 65) argue, prisoners welcome “supportive rather than coercive” interventions which “engage with [their] full personhood rather than trapping [them] in the amber of the past”. The reformulated framework distinguishes between the forms of ‘grip’ exerted by risk-reducing interventions in different penal circumstances. Table 6.1 (a) summarises its key terms.

A second conceptual touchstone comes from Fergus McNeill (2009), in a discussion of how supervisees experience probation supervision (see also McNeill et al. 2018), which links the pain/supportiveness question to notions of dignity and moral recognition. For McNeill, supervisees might feel helped, held, or hurt by supervision. To feel helped is to believe that, despite the status loss which inheres in punishment, one’s own needs are nevertheless recognised as meriting support. To feel hurt, conversely, is to believe that one’s needs are unrecognised: that punishment is only demotion. To be held is an ambivalent and intermediate position: constraints and demotions are frustrating, but tolerable to the extent that they are recognised to serve some legitimate wider purpose. The experience of being held may be prolonged, but is also temporary: that is, it depends on a tangible notion that after punishment, ‘moral rehabilitation’ (McNeill 2012) might occur. Table 6.1 (b) summarises the key contrasts.

| Demands made | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Less | More | ||

| Assistance offered | More | Supportive | Tight, firm |

| Less | Loose, neglectful | Lax, inconsistent, deficient | |

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Helping |

|

| Holding |

|

| Hurting |

|

In this framing, risk-reducing intervention might be ‘hurtful’, in the sense that it pushes for confrontation with the individual’s capacity for harm. But crucially, it might also feel like being ‘held’, if the subject believes the end is worthwhile. Conversely, to quote McNeill (2009 p. 10), if being ‘held’ fails to “bring about change”, then those who are held may conclude that their captivity aims for nothing more than the “contain[ment of] trouble”.

6.2 Assessed risk in the sample

This section summarises risk in the sample using an overview of different classificatory systems described in prison records. It shows how as a whole, the sample were believed to pose few risks of harm to others in custody, but that considerable uncertainties were prompted by the prospect of their release.

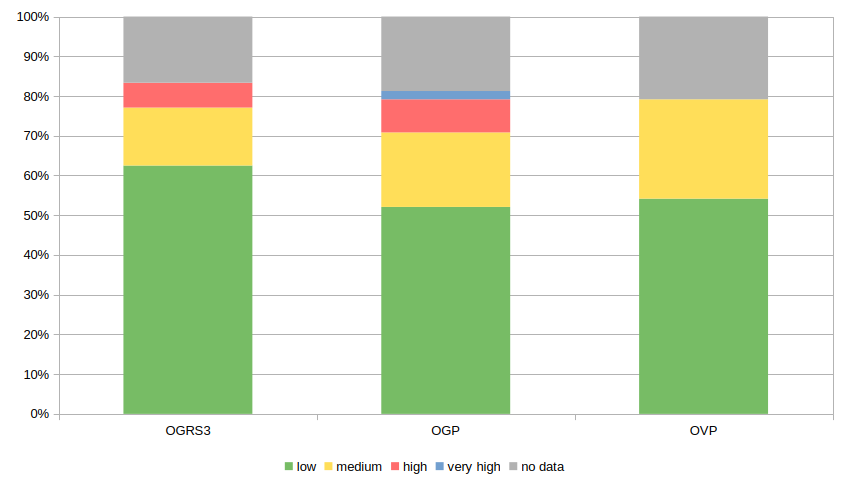

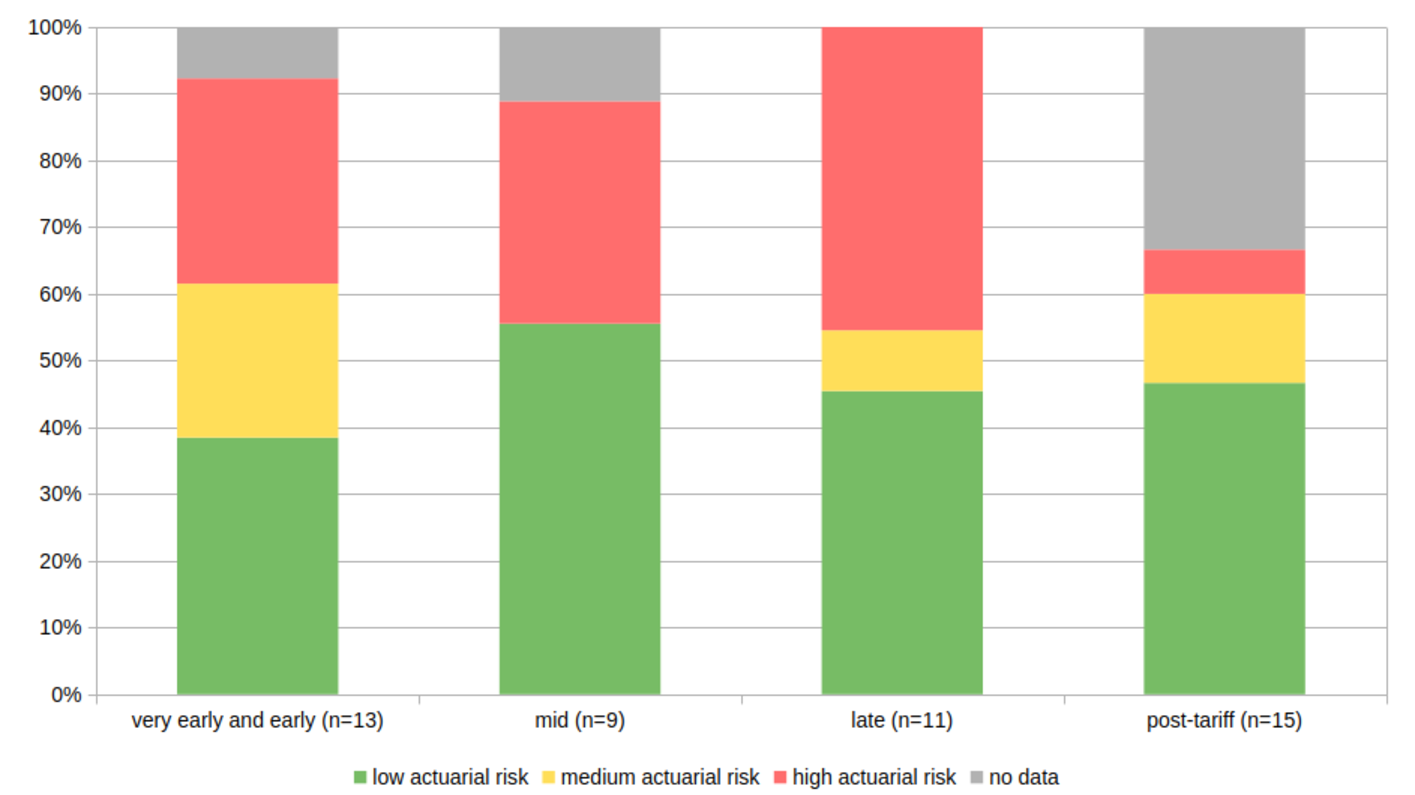

The Offender Assessment System (hereinafter, OASys) calculates actuarial risk scores for all lifers. Figure 6.1 summarises them, subdivided by assessment methodology (6.1 (a)) and sentence stage (6.1 (b)). Between half and two-thirds of participants posed a ‘low’ risk of reconviction. None posed a ‘high’ risk of reconviction for violence, and those assessed as ‘low’ or ‘medium’ risk outnumbered the remainder (which included missing data) by at least two to one.3 It is not evident from Figure 6.1 (b) that risk was lower among those later in the sentence: higher risk scores were evenly distributed across sentence stages, except in post-tariff, where missing data made it hard to discern a pattern.

Lifers in the sample had also been the subjects of Risk of Serious Harm (RoSH) assessments. Generated using a structured professional judgement (SPJ) methodology, the RoSH is more open to the assessor’s bias, but is also more responsive than the purely actuarial scores to dynamic risk factors. Its risk levels are more like categorical than continuous variables, in that they represent qualitative categories, though all RoSH assessments start from an actuarially-derived reference score.

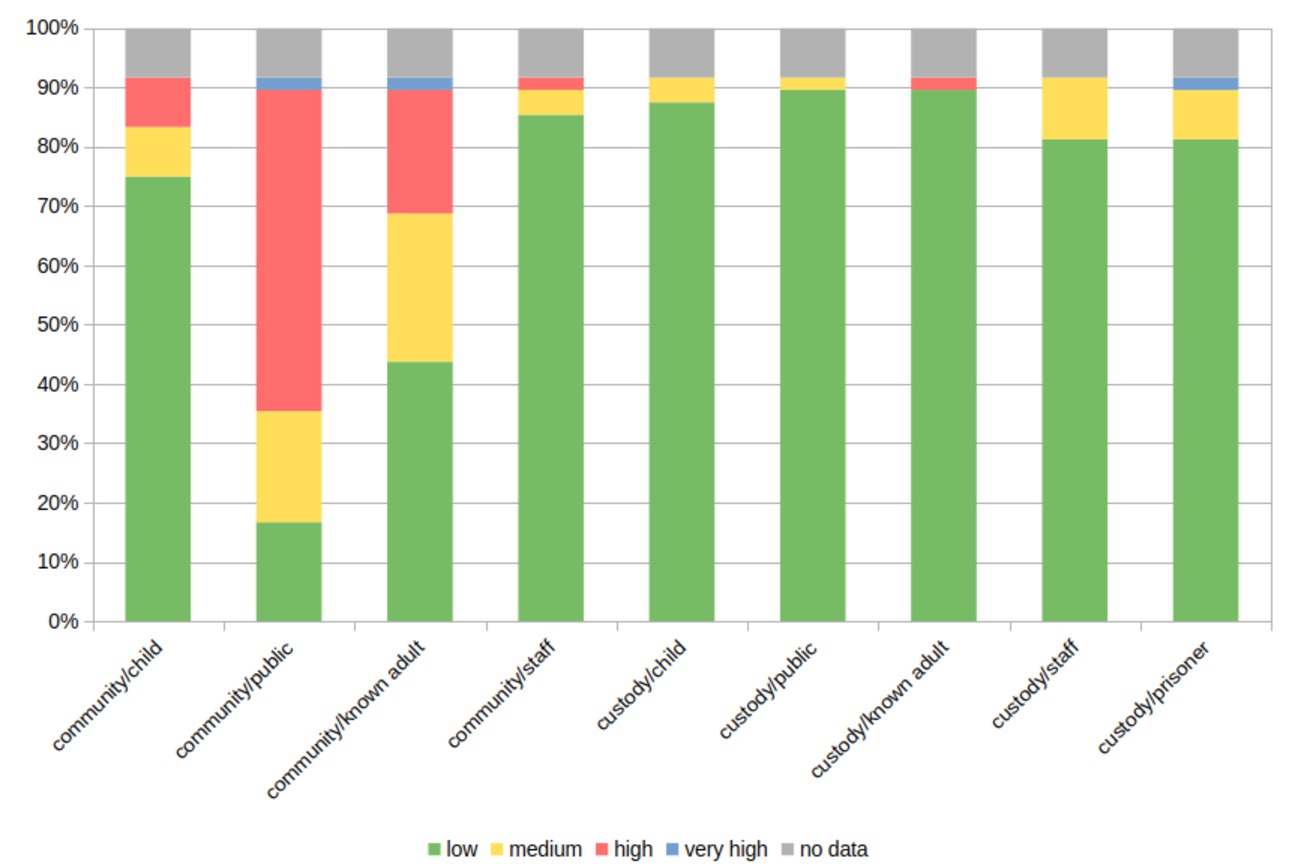

Figure 6.1 (c) summarises the sample’s RoSH classifications. Two main points should be noted. As the rightmost five bars show, over 80% had been assessed as posing a ‘low’ risk of seriously harming anyone in custody; only one individual had a ‘high’ or ‘very high’ assessment for any custodial group. These ‘low’ custodial RoSH scores are noteworthy given Swaleside’s reputation for violence, which lifers in the sample were not typically expected to participate in.

By contrast, the leftmost four bars of Figure 6.1 (c) describe community risk. Around half the sample were assessed at the ‘medium’, ‘high’ or ‘very high’ levels for RoSH to ‘known adults’, and more than 70% fell into these bands for RoSH to ‘the public’. Far fewer were expected to pose a risk of serious harm to children or staff, but those risks again exceeded those foreseen in custody.

6.2.1 Summary

What can be drawn together is only a crude sketch, which a random sample and a more methodical analysis would improve. At least, though, it is notable that staff expected over half of the sample to pose a ‘high’ risk of serious harm after release; but over half were forecast by actuarial methods to be at a ‘low’ risk of reconviction for violence. To draw out the implications: ‘high-risk’ status was assigned more because harm might be ‘serious’, than because there was a high statistical probability of it occurring.

The next section begins to explore risk communication at both prisons, by describing how they communicated with prisoners, and what they were like as morally communicative environments.

6.3 Swaleside and Leyhill as morally communicative environments

Offender management in custody, as described in the relevant policy framework, aims to “co-ordinate and sequence an individual’s journey through custody and post-release”. Its “primary purpose” is to “motivate [prisoners] and provide them with opportunities to change their lives and promote rehabilitation”. Staff are to work collaboratively with prisoners on a sentence plan “which is monitored, implemented, reviewed at points of significant change in circumstance from reception to the end of licence and post-sentence supervision” . Prisons should foster a ‘rehabilitative culture’: harmonious, collaborative, resource-efficient, minimally painful, and “reducing reoffending, protecting the public and preventing victims by changing lives” (all quotes from Ministry of Justice and HM Prison & Probation Service 2018 pp. 5–6).

The impression formed by these quotes is that the sentence plan and the activities it prescribes are an explicit moral code describing ‘pro-social’ conduct. Though its demands may be neo-paternal and ‘tight’, it offers ‘institutional hope’ (Seeds 2022), by implying that conduct aligned with its prescriptions will result, eventually, in moral and judicial rehabilitation. In fact, however, offender management communicated with participants in wildly inconsistent ways. This section describes how.

6.3.1 Swaleside—‘loose’, ‘lax’, or tight?

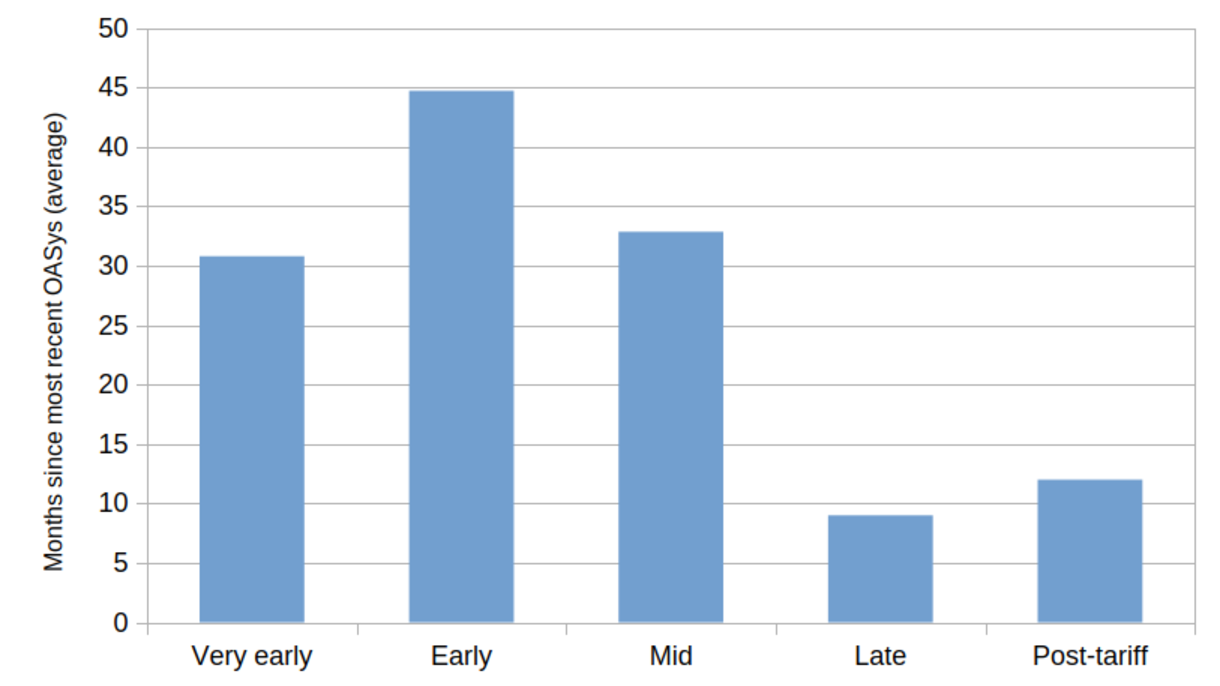

As Section 3.2.1 suggested, Swaleside’s OMU was struggling to implement offender management policies in line with policy. Casework backlogs were common, and the OASys (a key building block of the sentence plan) was often out-of-date. Figure 6.2 plots the average time elapsed since Swaleside participants’ most recent OASys assessment, subdivided by sentence stage. Only those in the late and post-tariff stages were being reviewed at less than two-yearly intervals,5 reflecting the prioritisation of high-risk and urgent cases described by the Inspectorate (see Chapter 2.3.3.3).

The result for many was confusion over how life sentences worked. One man expressed the belief that he was serving a determinate sentence, and that his parole eligibility date was a determinate release date. Many others were uncertain whether they had a sentence plan, or were certain they did not. This was not ‘tightness’, in the form of an “all-encompassing and invasive” power operating “closely and anonymously” and leaving prisoners with “the sense of not knowing which way to move, for fear of getting things wrong” (Crewe 2011a p. 522). Instead, its demands were few, half-hearted, and tenuously connected with risk and the offence.

6.3.1.1 Swaleside’s moral communication through documents

According to policy, all prisoners should have a sentence plan, listing recommendations intended to promote their progression (Ministry of Justice and HM Prison & Probation Service 2018). Yet of the 29 RC1 forms I reviewed at Swaleside, only four (all prepared for men in the late or post-tariff stages) listed specific ‘sentence plan recommendations’.7 The lists were short, vague, and sometimes seemed condescending, containing instructions such as “make constructive use of time”, “demonstrate appropriate behaviour”, and “understand likely consequences of offending”. They were targets calling for cooperation, not agency.

For the 25 RC1 forms which lacked ‘specific’ objectives such as these, the main explicit demands concerned ‘risk reduction work’. They, again, demanded vague and passive compliance, not agency. They also focused mostly on offending behaviour courses. The following is a typical example, quoted verbatim and in full. It is broadly representative of forms a) lacking sentence plan recommendations, written for b) participants not in the late and post-tariff phases, who had c) not yet ‘done their courses’:

- Risk reducing work completed

- No completed RR work

- Outstanding RR work

- Offending Behaviour - Appropriate accredited intervention programmes

- Resolve, if suitable

- TSP

- Kaizen if suitable

- Engagement with the Psychology team (ongoing)

- Engagement with the prison regime. Maintaining Enhanced status. Positive use of time. No adjudications or behaviour warnings.

Noteworthy here is the use of conditional (“if suitable”) and negative (“no adjudications or behaviour warnings”) objectives. ‘Success’ in attaining them entails no more than acquiescence to the basic routines of prison life, and engagement with programmes when the time comes.

Where the subject of the form had ‘done his courses’, the list was, if anything, even briefer. The following example is broadly representative of forms a) lacking sentence plan recommendations, which had been b) prepared for men not in the late and post-tariff phases, who c) had ‘done their courses’:

- Risk reducing work completed

- [list of completed courses obfuscated for anonymity]

- Outstanding RR work

- ETE8 (ongoing)

- Resolve (unsuitable)

- Pro-social modelling, gain enhanced status and use time constructively, remain adjudication free

None of the quoted objectives is SMART (i.e. specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound), as the policy requires; moreover, none of them list required actions supporting each objective in order of priority (National Offender Management Service 2015 para. 2.7).

These documents, for many participants and for years at a time, represented the only form of contact with the OMU about risk. They communicated little, and were detached from a meaningful assessment of day-to-day conduct. Many participants could not see any relevance between them and progression decisions. Grant, looking back to his time at Swaleside, put this crisply:

I just used to dutifully fill it in, put my little bit on there, post it back, and I’d get knocked back.9 The reason given is because my OASys isn’t up to date […] No fault of my own, it’s just that they haven’t done their job. I thought, “okay, fair enough, they’re busy”, you know? So the next one come through, I done it again… I’ve done about four or five… […] I was filling these bloody forms in and sending them back. I got another one, the OASys still wasn’t done, thought, “oh, fucking bollocks to that”, threw it in the bin. That’s when I got my C-cat! [laughs]

Grant (Leyhill, fifties, late)

The key point here relates to Swaleside’s moral communication. It demanded ‘risk reduction’, but did little to give these demands substance, or to link them with outcomes prisoners themselves found worth pursuing. It communicated broadly and vaguely, inviting but not expecting a response. Active participation by prisoners in the review process—another explicit policy expectation—appeared rare, and Grant was unusual in reporting having made such a response. Of the 29 RC1 forms I read at Swaleside, only one included written representations. These (paraphrased to protect anonymity) are worth reproducing in full:

What can I say? Last year, this form said you haven’t seen a change in me, but the person who wrote that has only met me in passing. I don’t see OMU staff though I make requests. If I take drugs or get in a fight you’ll take an interest and see a change, but I’m not ticking your boxes for the sake of it. I have changed: I help other prisoners with life skills, I’m self-controlled, calm, and I stay out of trouble.

Gary (Swaleside, fifties, early)

Of course, policies and RC1 forms represent aspirations, not manuals. Nevertheless, Gary’s reference to ‘box-ticking’ was significant, reflecting an impression that the OMU was interested only in changes fitting a template, not in changes prisoners might consider important. Also significant was that participants who (like Gary) accepted their guilt were often (like Gary) resentful of the OMU’s distance and lack of interest in them. They accepted the demand that they ought to change, but perceived indifference towards their efforts to do so.

The RC1 summarised one further form of explicit moral communication: positive and negative staff entries in P-NOMIS during the previous 12 months, reflecting conduct that staff wished to take the trouble to record formally, or which required censure. Almost without exception, positive comments related to compliance: courtesies to staff, facilitating the smooth functioning of the prison, or representing Swaleside positively to outsiders. The following items, selected from three separate RC1s, are representative:

- compliant and polite while uncuffed on escort

- worked additional hours

- always very helpful and polite to staff

- helped me greatly by meeting with the family of [name] who recently died

- always polite to staff and if asked to do something never says no or complains

- alerting staff to an offender who was found unresponsive in his cell

- active role in wing spring clean and engaged in plenty of banter

Only the first item in this list directly indicates anything about the prisoner’s capacity to manage his risk, and then only in a very specific situation. Correspondingly, negative entries (which were much more numerous) mostly related to obstructions of official control over prison life. Discourtesy to staff, incidents of non-compliance, specific rule breaches (such as failed drug tests), and adverse adjudications were all common themes, and usually recorded without context.

A vague sense of pro-sociality lies beneath the positive entries. Doubtless the praise and appreciation expressed were genuine, and many negative entries recorded similarly undesirable behaviour. But the point to note here relates, again, to communication and ‘tightness’. Neither Swaleside’s OMU nor its uniformed staff were communicating ‘tight’ demands in relation to risk, and the overall impression is one of low, undemanding expectations. It was extremely unusual for case notes to record achievements participants themselves rated as personally important, even when these reflected major changes of lifestyle or when (as in Gary’s case above) they tried to positively influence others:

Prisoners seem to give you more kudos than the staff and the establishment […] Like, they’re quick to slap you down for the least little thing […] [but] I checked, and [my Open University degree] wasn’t even on my NOMIS […] They take no account [of] it.

Leon (Swaleside, forties, mid)

Summing up, it is helpful to think of these encounters—between individual lifers and their documents—as ethical interactions. Particularly in interpersonal contexts, but also between persons and institutions, anthropologists have shown interaction to be:

…in itself a moral and ethical domain. When persons interact they necessarily and unavoidably assess whether they are being heard, ignored, disattended, and so on. Is this person really listening to me? Paying attention to me? And, in so doing, acknowledging me as a worthwhile person who merits such attention?

Sidnell (2010 pp. 124–5)

Swaleside’s implementation of the offender management framework was distant, unresponsive, and inattentive. It made vague demands, and rewarded compliance unpredictably. Many participants understood risk to be the prison’s (not their) concern. They often accepted the idea that their offence meant they ought to change; but in the face of disregard they looked elsewhere for ethical validation.

This was, then, the overall style of communication at Swaleside. The following sections consider how three different prisoner groups perceived it, differentiating them by how they understood Swaleside’s distinctive way of communicating with them.

6.3.1.2 Perceiving ‘looseness’ or ‘neglect’

How prisoners at Swaleside perceived the prison’s communication depended largely on their sentence stage and prior custodial experiences, especially whether Swaleside alone had shaped their ‘penal consciousness’ (Sexton 2015), or whether they could compare it with other prisons. Two subgroups perceived the prison’s treatment of them to be ‘loose’ (in the conceptual terminology unpacked in Section 6.1).

For one subgroup, held in the early stages of the sentence and usually having come directly to Swaleside from a remand prison, the prison’s communication felt ‘loose’, in the sense set out in Section 6.1. They felt the prison proffered little assistance, but also that it was making few demands:

I don’t know what my sentence plan is […] I just get my recat paper [i.e. the RC1] every year and they tell me you ain’t done no courses. I ain’t got a clue what I’ve got to do […] [T]hey just leave you to it.

Yakubu (Swaleside, twenties, early)

Some described this treatment as “neglectful” (Ebo)—a suggestive term, pointing to a more powerful party’s failure to fulfil obligations:

[I hate how] they are so blasé about it […] My probation came to me and said, “I’ve only got your pre-sentence report.” I’ve been in jail TEN YEARS. How is the only thing you’ve got on me my pre-sentence report? I’ve done so much […] to better myself, to get myself in a good position. They turn around and say to me, “Oh, well, I don’t really know what you’ve been up to.”

Ebo (Swaleside, twenties, mid)

Ebo’s complaint was not that the OMU made moral demands, but how: vaguely and without interest in his response. Swaleside’s laxity felt to him like a failure of reciprocity (a psychological foundation of the capacity for ethical behaviour—see Keane 2016 pp. 39–58). Ebo (and others) felt that working to improve oneself ought to attract recognition. These criticisms tended to focus not on staff but on ‘the system’, or the state. Its failures fell short of outright abandonment,10 but by withholding moral recognition and a map to restoration, it communicated indifference and disregard, weakening its claim to the moral standing to deliver censure. The subgroup to which Ebo and Yakubu belonged—mostly, men from London, convicted young, now in early or mid-sentence in their twenties and thirties, and resident at Swaleside for at least a few years—felt ignored. For those later in the sentence, the resulting frustration metastasised into a kind of sullen cynicism, and refusal to engage:

This jail here, this jail is a dumping ground. They don’t care about you, you’re just here, you’re paying their wages. Do you think they really care? […]

So any priorities [OMU staff] might say they’ve got for you…

[Angrily] They haven’t GOT any priorities. This jail—any jail—they blow smoke up your arse.11

Nixon (Swaleside, forties, post-tariff)

It seemed to them that the prison expected little more than a performance:

You know what I noticed? When you get sentenced, they want you to spaz out—20,000 nickings, fighting, kicking off, phones, drugs. They WANT to see that. Then the last 5, 6, 7 years of your sentence, now you change, get Enhanced for a few years. You go get your mandatory piss test; you pass it. You know what I’m saying? They’re thinking, “Oh yes, we’ve seen a change now”.

Courtney (Swaleside, forties, late)

A second analytical subgroup who perceived ‘looseness’ in Swaleside’s communication with them comprised men convicted when older. Their assessed risk was typically lower, and they had either been found unsuitable for offending behaviour programmes, or had completed them willingly only to find the prison’s grip on them relaxing. As with those who bemoaned the prison’s ‘neglect’, there was an underlying desire: to be recognised as ethical individuals, not as the representatives of impersonal, risk-bearing groups. But they, too, found that the OMU communicated few explicit demands and made few attempts to discipline their subjectivity. Its prime demands were obedience and compliance:

Does it feel like they make demands on you?

It’s just the courses I get told to do. […] And then they come back: “he’s not eligible for it.” And then it’s, “Terry keeps himself to himself, he’s polite”. And all that.

So what really matters to them?

Don’t go out there messing around the system and playing up.

Terry (Swaleside, fifties, mid)

I have nothing more to do, I’ve completed my sentence plan. […] My latest sentence plan basically just says stay Enhanced, keep working, and follow what they call the pro-social model. That’s it.

What do you think they mean by that?

Just be a good boy […] The OMU system is not set up to recognise anything more.

Rafiq (Swaleside, thirties, early)

Not everyone at Swaleside perceived the prison to be ‘loose’; two subgroups perceived matters differently.

6.3.1.3 Perceiving ‘laxity’

The first was the handful of men for whom Swaleside represented a progressive move. During many years in maximum-security prisons, they had encountered clearer, higher expectations, and (more importantly) intrusive, even oppressive staff supervision. Such conditions were paradigmatically ‘tight’; progressing from them required an intense, unyielding commitment to play the game in one’s own interests:

A decision comes: either you lock off the past, you decide you’re gonna move forward, and you do your courses and work for your own future, or you don’t. You can stay in prison and be a wanker, or you can lock off and get out.

Mark (Swaleside, thirties, post-tariff), from interview notes

As we saw, lifers who had only spent time at Swaleside tended to believe that risk management was a kind of charade, unrelated to their actual sentence progression. This was far from true for those with past experience of cat-A conditions:

Obviously my last sentence plan at [category-A prison], they set me goals. I’ve achieved most if not all of those […] So they need to set me some new ones […] It’s like, “stay out of trouble, continue education”, yeah? That’s kind of vague. […] I do believe I need a bit more structure.

Leon (Swaleside, forties, mid)

Former cat-A prisoners at Swaleside were typically also well-informed about national policy, and some used complaints to force their own case management into line with policy. They also took care to curate, manage and correct information in their files, a striking habit evident only among this group:

My last OASys was in [category-A prison] because they only do it every three years here, which is bollocks. Now, eventually I’m going to move on somewhere else. Who’s going to put all that into my OASys, all the good stuff I’ve done on this wing? It’s going to get lost. Obviously, there’ll be bits and pieces on NOMIS, but there won’t be no reports done. I’ll get to another jail and they’ll talk about, “what did you do off the plan?” No one in that jail’s going to know what I did unless I tell them.

Tony (Swaleside, thirties, mid), from notes

It was not simply experience of category-A status which mattered here, but more generally, experience of the ‘crunch points’ associated with recategorisation and progression. Life sentences are now so long that periods of ‘dead time’ may be unavoidable, but ‘crunch points’ are periods of intensified scrutiny. Those at Swaleside who understood this had either downgraded from category-A, or been knocked back for progressive onwards moves, because past incidents on file had complicated their progression in unforeseen ways. A ‘crunch point’ increased their awareness of the pervasiveness and reach of risk assessment—the ‘power of the pen’ (Crewe 2011b). Those who had spent most of the sentence at Swaleside appeared more unaware of this. Crunch points—when risk was sharply in focus—were exacting and demanding, unsettling the feeling of ‘neglect’ which prevailed at other times, and rendering the prison’s indifference hitherto both less benign and more damaging, in hindsight. Former category-A prisoners understood that not just compliance, but a formal record consistent with a narrative of reform, were preconditions of progression. To them, Swaleside felt not ‘loose’ but ‘lax’ (Crewe and Ievins 2021). It made demands, but those with experience of ‘tighter’ conditions understood only too well how vaguely and unhelpfully they were communicated.

6.3.1.4 Perceiving ‘tightness’

A second subgroup who experienced something other than ‘looseness’ at Swaleside were receiving treatment in the PIPE unit. Often having been recategorised as category-C prisoners, but still held at Swaleside, they usually had sustained experience of other prisons and earlier ‘crunch points’, and many were in the PIPE specifically to ‘catch up’ with risk-focused sentence plan objectives. They, like the former cat-A men, were accustomed to being gripped ‘tightly’. However, the additional clinical resources in the PIPE meant their current experience was of a close—and supportive—style of communication:

My clinician said, “all those were just feelings you brushed off because you did not understand them”. She made me look at them all. But not just, “there they are, now move past it.” It was, “Look at them.” And you look at them through a pair of glasses, then through binoculars and a magnifying glass […] Bloody hell… She was so good. So, so good.

Tom (Swaleside, fifties, post-tariff)

Even in the PIPE, though, there was a sense of diminishing returns. Too much intervention could tip over into outright resentment:

I eventually got to this fucking place and then they come to see me. And then I said, “well, how long am I going to be there?” “Twelve months.” Yay, twelve months, alright!

When was that?

Three years ago! Well, a bit more […] They said I don’t have any remorse. But I don’t give a fuck any more […] I mean, I’ve… I used to feel bad about what happened […] They tried to… drive me into depression, almost… […] And then they go, “well, you haven’t got any remorse”. I used to have, but you bashed it out of me. I used to care. I don’t give a fuck any more.

Chris (Swaleside, sixties, post-tariff)

6.3.2 Leyhill—‘tight’, demanding, and entangling

Where Swaleside communicated a morally minimal indifference (comply, keep out of trouble, but otherwise do as you like), Leyhill intensified supervision and conveyed distrust.

This place is scared of its own shadow.

Fred (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

Leyhill’s treatment of risk entailed a very different style of communication. Participants arrived expecting something close to ‘moral rehabilitation’ (McNeill 2012): restoration to a more trusted, less dishonoured form of subjectivity. Yet in being labelled as ‘risky’ and subjected to supervision, they perceived renewed condescension and stigma. Lacking Swaleside’s situational security controls and suite of interventions, Leyhill’s resettlement function involved a structured, cautious restoration of trust, backed with careful monitoring. The prison ‘responsibilised’ participants, and its individualised behavioural expectations far exceeded Swaleside’s in specificity and scope.

However, there was a profound ambivalence about risk there. Any one of a number of several explanations could explain the widespread compliance of prisoners there. Which explanation was ‘true’ was difficult to interpret. Compliance might signal genuine reform; or that a prisoner was ‘gaming’ the system; or that he was concealing risky behaviour; or that offence-relevant situations which might bring risk into focus were absent.12 Mistrust was therefore institutionalised at Leyhill, because it was so hard to know whom to trust.

As a result, the move to Leyhill did not long retain the impression of being a ‘progressive’ one towards freedom. Several recent arrivals expressed surprise at how they felt there:

…he expected it to be “less like a prison” […] the OMU “would still make your life pretty difficult if they don’t take a shine to you”

Jeremiah (Leyhill, thirties, post-tariff), from notes

Many participants believed the prevalence of sexual offence convictions at Leyhill was the key issue driving this caution. Among the evidence they offered was the lack of good-quality ROTL work opportunities:

There’s no [outside] work here, It’s all bollocks […] It’s not like other D-cats. I can understand why, because of the clientele, but no, it’s not helped with me.

Ron (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

Leyhill therefore felt not only ‘tight’, but also staining (Ievins 2023). Stricter risk controls prolonged and reinforced a message of lowered status. For participants who did have sexual convictions, life there resembled a kind of non-life or undeath (Ievins 2024), offering existence but not space in which to pursue what really mattered:

It’s Groundhog Day […] guys [here] that know each other, every time we pass each other, we go, “Unnnnggghhhhh!” [miming a lifeless demeanour] Zombieland—it’s Zombieland! Because there’s nothing to look forward to here, nothing. […] I’ve got friends that […] actually fucking dread [day releases] and the rigmarole they’ve got to go through, and the mistrust they endure when they come back […] They go, “it’s more hassle than it’s worth.”

Fred (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

The mention of ‘mistrust’ here points to a significant gap: between the expectations and the realities of resettlement and preparation for release. In policy, the purpose of ROTL is clear: to test compliance with licence conditions, and thereby to gauge risk. Prisoners, however, were impatient to make up for lost time, and to put gains during the sentence to effective use:

I’ve gained an education. Like, better qualifications. I didn’t have anything when I came inside […] You know, I want to do good. I want to, you know, complete things. Don’t want to start something and not finish it […] Like, work and stuff… […] Yeah. So, like, [release] just opens up, like, so much possibilities.

Jeremiah (Leyhill, thirties, post-tariff)

6.3.2.1 Leyhill’s moral communication through documents

The risk documents reviewed at Leyhill—principally, Enhanced Behaviour Monitoring (EBM) assessments13 and ROTL risk assessments—corroborated the impression that conditions ‘tightened’ upon arrival there. It is impossible, for reasons of space and anonymity, to quote these records at length. But an indication of how differently risk was constructed at Leyhill than at Swaleside can be seen in Table 6.2. It presents a composite of two participants’ records, paraphrased and intermingled (to obfuscate identity) as though they described one person. Both participants’ actuarial risk scores were “low”, and their RoSH assessments were “low”, except for “high” risks of harm to the public:

| Behavioural indicators of risk elevation |

|

| Behavioural indicators of risk reduction |

|

The examples in Table 6.2 focus mostly on emotional self-management. With other records, the underlying structure was the same, but the behaviours they classified as encouraging or concerning differed. Substance misuse, perceived misogyny, or personality traits such as ‘argumentativeness’, along with many others, were all associated with variable risk. Also noteworthy is the importance given to positive relationships with staff, who are presumed to be able and willing to offer time for support and guidance. Staff are presumably also given some discretion about what constitutes “helpful” or “unhelpful” thinking, or “appropriate” problem-solving. Participants are placed in a relationship of quasi-dependency on them, who are to be relied on for advice, guidance, and (presumably) identification of further needs.

Just as for former category-A prisoners at Swaleside, then, the transition to open conditions represented an ethical ‘crunch point’. The removal of situational controls brought new risks into focus, specifically those associated with the resettlement process. Risk assessors approached their task with a renewed caution, and the transition entailed an unexpected element of prescriptiveness in the risk controls applied to participants, some of whom expected them to be relaxed. The freedoms of the open environment, anticipated by some as the forerunner of restored trust and greater moral recognition, therefore in fact signalled conditionality, surveillance, and constraint. Leyhill felt to them much closer to ‘tightness’ as originally described by Crewe (2011a), than to the ‘looseness’ or ‘laxity’ identified here with Swaleside.

6.3.2.2 Differing attitudes to ‘tight’ constraints

Although cross-sectional data can only offer pointers, it is not implausible to think of crunch points—i.e. periods of ‘tight’ high expectations—acting as a kind of sorting mechanism. Some participants at Leyhill had spent prolonged periods in ‘looser’ and ‘laxer’ prisons. Left comparatively free to dream about the future and develop their own plans and expectations, many had developed ground projects and ethical practices featuring redemptive, optimistic narratives familiar from desistance research. Dalton’s aim was to make a living from music. But as he put it:

They’re saying, “Yes, but what is the achievable goal?” I’m saying, “Well, that is achievable. How do you think there are artists? Because they set out to achieve it, and they’ve achieved it. It’s not achievable if I don’t try to achieve it.” They’re like, “Yes, but […] it’s not going to look realistic […] What else could you put?” I’m saying, “How do you know I can’t do that? Don’t tell me what I can and can’t do.”

Dalton (Leyhill, thirties, mid)

For some, then, ‘tight’ risk management smothered ambition and imposed alienating lifestyles of minimal risk and minimal reward. Some found this difficult to accept, pushing back and laying claim to bigger ambitions:

I have got an [offer of work with a professional firm] on an unpaid basis. […] I would sooner do that than work in a placement where I am making low-end money, but no personal progression going on. Whereas, if I went and worked with [them] my CV starts to build and I start networking […] I am not automatically barred […] I have looked into it […] I have had the paperwork sent through […] But it is [outside the travel radius] [so the prison said no].

Dario (Leyhill, forties, late)

Those harbouring ambitions of this kind had generally been relatively young at conviction, and expected to be released during their thirties and forties. Older men, or those so far over-tariff that they had learned not to hope, found ‘tight’ risk management more of an irritant than a kind of thwarting. Most said they wanted little more than a simple life after prison:

They want to put me in a hostel on home leaves to watch me, but they’re not going to see anything. Just an old man going to church and reading the newspaper.

Emlyn (Leyhill, seventies, post-tariff), from notes

I mean, obviously, I’m going to have to go where I’m told to go, basically. Earn some money—I don’t mind how. Get a German Shepherd dog. Take it for walks. That’s all, really.

Grant (Leyhill, sixties, late)

The contrast here was between younger men who wanted to transcend their sentence, and saw risk conditions as an obstacle, and those who wanted simply to enjoy life within constraints. Similarly, those who had internalised the view of themselves as damaged and dangerous described patiently continuing in their ground projects of disciplinary self-monitoring:

At the time of my oral hearing we were requesting release or open conditions. I am glad I didn’t get my release now. Even more so now I am here, and I am gaining that experience to what it is like outside and how that affects me as a person.

Nicholas (Leyhill, thirties, late)

The difference here—between those at Leyhill who were frustrated by ‘tight’ controls and those who were not—tended to relate to the moral status of the offence for each individual, or to their position in the life course. Either variable could make the risk controls appear reasonable or absurd.

The remainder of the chapter sets out a typology of individual ethical responses to risk management. First, however, I briefly summarise this section on how the two prisons communicated morally with participants.

6.3.3 Summary—moral communication across the two sites

Moral communication at Swaleside used a language of risk, but substantive demands were few: be available for prescribed interventions, reproduce prison order, and engage constructively with staff. Prisoners who complied, made few demands, and challenged officers infrequently were left alone; those who did not were written up. Few could see how this might generate negative consequences later, when ‘crunch points’ arose in relation to their progression, but some—chiefly former category-A prisoners—did, and sought to work on their records as a consequence. Leyhill, by contrast, used a ‘tighter’ application of power than Swaleside. Some there felt entangled, perceiving a thwarting of plans their record of compliance had earned them the right to pursue. Others largely accepted, and sometimes even found benefit in, the ‘tight’ measures of risk management they were subject to.

Understood via a synthesis of evidence considered in this section, moral communication at the two prisons can be described in relation to the overriding concerns of the respective OMUs: to reduce and contain threats to prison safety (Swaleside) and to gauge and manage threats to public safety (Leyhill). These are neatly characterised as ‘correctional risk’ and ‘community risk’ by Kazemian and Travis (2015 p. 363), who note that LTPs “do not necessarily pose a significant threat to either”, and suggest that politicians and the public are more typically concerned by the latter.

The contrast is critical here, too. Most participants at both sites, like most lifers in general, were ‘easy keepers’ (Herbert 2019) compared to shorter-term and more volatile populations. Containment, not transformation, was a feasible and logical response to their risk, with sentence lengths putting disciplinary ‘crunch points’ many years in the future. This was most evident at Swaleside, which intervened parsimoniously, making few, and mostly formulaic, demands. Some prisoners perceived ‘looseness’ in this (i.e. few demands, little support), others ‘laxity’ (i.e. high demands, low support). At Leyhill (and among some late-sentence and post-tariff prisoners at Swaleside), the potential drawbacks of this distant, vague communication became apparent. Since the real determinants of sentence progression seemed beyond their control, many of the sample followed moral codes not linked to risk, but to their own understanding of the offence and their personhood. But shifts in official thinking, from managing ‘correctional’ risk to assessing ‘community’ risk, brought with them different and far ‘tighter’ forms of governance. Many participants found this perplexing, following many years in which they had been allowed to think that remaining ‘easy to keep’ was enough to progress.

These insights, crucially, arise from being able to consider the issue through two kinds of evidence. Mona Lynch (2015 p. 277), describing research on a 1990s US parole office, noted that documents sought “to keep track of and manage” parolees, not “transform them”. In this study, as in Lynch’s work, the key analytical contrasts are between documentary and interview data, but the contrast between sites also points to moral communication which varied in style, intensity, and individualisation depending on prison type and function.

Why did ‘loose’ or ‘lax’ conditions feel comfortable to some, while others found them neglectful, absurd or complacent? Why did ‘tight’ conditions fit some participants comfortably, even as they chafed or entangled others? These questions—relating to the perception of risk governance, and the ethical stances taken up by individuals in relation to its demands—are taken up in the next section.

6.4 Four ethical responses to risk governance

This section typologises four ethical stances towards risk management, characterising each in terms of whether participants felt ‘helped’, ‘held’, or ‘hurt’ by it. The focus is on how participants appropriated the demands of penal power. I sketch four styles of engagement with the sentence plan, differentiated by how they articulated feelings about the offence, the intervention, and the future, as follows:

- Prisoners who ‘resisted the tide’, for whom:

- the sentence persecuted them, as innocent men

- risk interventions offered nothing but ‘hurt’

- ethical self-care managed the resulting pain and frustration

- Prisoners who ‘trod water’, for whom:

- the length of the sentence was its most salient aspect, with progression temporally distant

- risk interventions, expected to be ‘hurtful’, were best delayed

- ethical self-care consisted in putting off its demands and making the most of ‘dead time’

- Prisoners who ‘drifted’, for whom:

- the sentence communicated censure they chose not to accept, and dangled incentives which did not interest them

- risk interventions neither ‘helped’ nor ‘hurt’, and could be safely ignored

- ethical self-care consisted in marking out and pursuing private, and often metaphysical, accounts of ‘the good’

- Prisoners who ‘swam onwards’, for whom:

- the sentence felt legitimate, and hope felt credible

- risk interventions could be ‘helpful’ or ‘hurtful’, but were at least yielding progression

- ethical self-care consisted in harnessing their purposes to those of the sentence

6.4.1 ‘Resisting the tide’

With few exceptions, those who ‘resisted the tide’ also maintained innocence. Resistance to blame entailed resistance to classification as a dangerous person who ought to change:

So they said that Nasim’s past and current convictions are evidence of a lack of respect for society and the law […] And this is all nonsense because there’s no evidence in this conviction [for me having] a lack of respect for society and law.

Nasim (Swaleside, forties, post-tariff)

Descriptions of risk management among those who ‘resisted the tide’ conveyed little, beyond a sense of being ‘done to’ by hostile, uncaring structures:

They decided that I should do TSP, because I don’t have any previous […] They also suggested that I should do Victim Awareness and Healthy Relationships. There’s no arguing with them […] I’ve told them that they are basing this on OASys that’s full of mistakes […] but they said, “Well, we don’t have anything else to go on so we’ll use that and we don’t care.”

Janusz (Swaleside, thirties, mid)

Claims of innocence rendered the prison’s methods intrusive and coercive. Janusz’s resentment was particularly strong (“if I don’t, I won’t be released”), and he was aggrieved by the prison’s indifference to dialogue (“there’s no arguing with them”). Constraints imposed to manage risk were ‘hurtful’; the idea that they might be ‘helpful’ was alien to the sense these he and others had, that they were already ethical beings:

This is where I’m trying to say to them, “Look, what do you want me to change?” […] You can’t change a violent or bad person by leaving them in this environment.

Courtney (Swaleside, forties, late)

Attitudes to the offence, then, were centrally implicated in how participants responded to demands for change. Attitudes to the future could also affect engagement with the sentence plan. This was stark with older participants, who were nonplussed by the prison’s interventions to manage risk, since they usually expected to be very old by the time of their release:

I can’t understand why [if] you don’t do the course you can’t be released. You are still the same person either way. If I knew I had to do twenty years…14 Pffffff… I don’t think I would bother to do it, you know. What would be the point? […] Easier to have done myself in.

Olivier (Swaleside, sixties, very early)

A governor here on a risk board said it was going to be on my licence that I could never get married again. Fine! I’m not at that stage of my life, am I?

Emlyn (Leyhill, seventies, post-tariff), from notes

When incentives linked to progression and release had a genuine appeal, attitudes to intervention could shift, and ‘resisting the tide’ could give way to a kind of strategic bargaining. Ian (whose decision to take responsibility for his risk, but not for murder, was described in Section 4.2.3.1) and Saeed both wanted to rebuild relationships with family members. They found ways to accommodate the prison’s demands via a balancing act: compromising on the notion that they ought to change, but not on the claim of innocence. This meant ‘wearing’ aspects of the selfhood defined by prison records, and working on this in OBPs:

I think I’m the only one on the [offending behaviour] course who talked about a different crime, my ABH.

Saeed (Swaleside, forties, early)

The subject position of the ‘innocent but reformed’ lifer was striking. There was no sense of ‘redemption’ regarding the offence, nor an internalisation of risk. However, strong moral codes emphasising gratitude, humility, reciprocity, and interdependence were often evident, and fostered a virtue well-suited to the wider situation: that of making the best of a bad lot.

I still… I eating every day. Alhamdulillah, shukr alhamdulillah, praise to God!15 If you go to my cell, I have everything. Milk, cereal, fruit… All fruit. You see my bed. Nice bed. TV. Phone. Alhamdulillah, there’s some people that have worse than this life outside!

Saeed (Swaleside, forties, early)

Such expressions of gratitude and powerlessness sought to transcend ‘hurt’ and ‘help’, bypassing the prison’s moral code and referencing another. However, they were unusual in the sample, and overall those who ‘resisted the tide’ were typically angry and resentful.

Men who maintained innocence asserted their ethical status regardless of the conviction: they wanted to preserve pre-prison selfhood and clear their good names. Ground projects associated with legal appeals were common among those early in the sentence. Among those later in the sentence, when (for many) the quest for vindication was becalmed by procedural or financial constraint, ground projects relating to self-preservation developed, often with an emphasis on preserving health. In all cases, however, the moral demands of risk management and reform were held as far away as possible:

I ain’t going to lie, yeah… I haven’t really tried to understand nothing in prison. Like, I’ve got assessed for courses […] CALM, ETS, all of them courses […] They say IEP this, and get that form, and this form, and […] I don’t want it. I’m not trying to… I’m not trying to take anything in. I’m not trying to act like I understand, I’m not trying to learn about prison […] I’m not trying to soak none of this in.

[…] You’re keeping it at arm’s length.

Keeping it at arm’s length, mate! [laughing] Fuck arm’s… if I can get a broom I’ll get a broom […] Bargepole, whatever I can… Just keep it at a distance, man.

Reuben (Swaleside, thirties, mid)

As Saeed and Ian suggested, though, such adamant denials of culpability could yield to something subtler and more qualified, where desired outcomes might accrue from the effort.

To summarise: ‘resisting the tide’ meant rejecting demands to reform oneself and manage risk, on the basis that they were unwarranted. The challenge in sustaining this stance was that prison life was entirely structured around legal guilt. Appeals—the only conclusive means by which to avoid ‘wearing’ the offence—were inaccessible, exhaustible, and beyond control. Thus, staunchly ‘resisting the tide’ early on could sometimes yield to bargains and accommodations with risk management later on; this subtly modifies the description by Crewe et al. (2017) of ‘swimming with the tide’ as a form of offence-related moral accountability.

6.4.2 ‘Treading water’

For a second group, the key ethical considerations were tariff length, material conditions and ‘outside problems’ (see Chapter 2.4.2) such as family relationships. These considerations militated against compliance with the demand to confront the offence and reduce risk, for the time being. ‘Resisting the tide’ involved pushing back against censure; ‘treading water’ involved no such resistance, but instead delayed self-scrutiny, in favour of ground projects not related to the sentence plan.

Those who followed this path were mostly at Swaleside and in the early and middle reaches of the sentence. Exceptions were found among those who, at either site, were over-tariff with no clear sentence plan objectives, and who were simply waiting for the next parole review:

I’m just waiting, ain’t I? It’s a waiting game […] I thought I’d come in and get a job, go out and work, great, get some money, save up. No. It’s a waiting game.

Ron (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

‘Treading water’ was also common with those serving longer-than-average tariffs, or who had been assessed as low-risk. Both conditions increased the anticipated quantity of ‘dead’ or ‘nothing time’. Matt was very early in a multi-decade sentence:

Do you have a sentence plan?

No.

You don’t, or you don’t know?

No, no, no, no, no. There’s no sentence plan. No need.16 Got waaaaay too long […] I’m going to be a pensioner when I get out. You know, there’s no cause to.

Matt (Swaleside, fifties, very early)

Low-risk status also implied ‘nothing time’, because those who had it were often found unsuitable for interventions, for cost-benefit reasons: OBPs might not alter their risk enough. Low-risk status felt ‘loose’, with ‘crunch points’ feeling a long way off:

Do you have a sentence plan?

I don’t know. […]

When did you definitely last have one?

In 2015.

What was on it?

“Complete TSP. Remain IEP- and adjudication-free. Maintain employment.” That was about it […] My risk levels are low across the board. […]

So what does the prison want from you?

I don’t know. This place is strange […] They’re quite happy to just leave you and let you do your own thing.

Adam (Swaleside, twenties, mid)

Adam and many others had drawn the conclusion that little or nothing was expected; that risk assessments carried few consequences and appeared to involve the prison ‘talking to itself’:

All they’re getting [i.e. risk assessors] is what these guys [i.e. staff] on the wing, like, put on a sheet. So I’m not sure what ‘risk’ is supposed to be […] They’ve got to get to know you, surely?

Robert (Swaleside, fifties, early)

They concluded that Swaleside only wanted them to ‘keep their heads down’. Where decades of the sentence remained, doing so would be easier and more comfortable in some prisons than others. Many preferred not to be transferred to category-C prisons, believing the cat-C estate to be dangerous, uncontrolled, potentially progression-risking, and a less amenable environment than the LTHSE.

Participants who ‘trod water’ were willing to work on their risk. They differed from those who ‘resisted the tide’ in that most accepted at least a qualified kind of guilt. They expected to ‘play the game’, but not yet; or had completed the work recommended for them and had time left over. Some worried explicitly about stagnation, and perceived it to be an unavoidable feature (not a bug) of the sentence, with the following anecdote offering particularly striking support for this idea:

When I was at [HMP X], [the Prisons Minister] visited. The staff arranged for him to come in and talk with prisoners and staff. […] I said to him, “Excuse me. Could you answer a question for me please?” He went, “Yes, if I can.” I said, “I am a long-serving prisoner. I have completed all of my courses and I have a long time left to serve. I have managed to get to a C-Cat prison. However […] programmes-wise [the sentence plan] is all completed. Is the government planning […] to put anything in place for the rest of that period […] to prevent us from stagnating?” And he said, “Well, you are just going to have to get on with your time, aren’t you? I am sure you have a couple of bodies lying around somewhere.” And he walked off.

Dario (Leyhill, forties, late)

Thus, ‘treading water’ was defined not by opposition to the sentence, but by passing time as profitably as possible. It prioritised finding (or retaining access to) ‘niches’ (Toch 1992/1977), to the extent that they were available, in which pleasure, self-improvement, or the acquisition of new skills was feasible. ‘Food boats’ (see Earle and Phillips 2012 pp. 146–7) were a recurrent theme, as was artistic production:

I’m getting the books, I’m starting to read them, and, you know, I can read music! I mean, not very well… I can tell you what the notes are, and where they appear on the guitar neck, you know? And it’s just… Just learning, really.

Matt (Swaleside, fifties, very early)

These activities all had the goal of consuming time convivially, or of using it to develop the self. Others were rooted in well-being and self-care. Gym work was commonly described as a way to pass time, and connected with longer-term objectives of sustaining good health for life post-release. For some, academic study often produced a sense of counterfactual self-exploration, and of working out whom they might have become:

[My degree] kind of opened up my eyes a little bit that I had been… let down by society and that if I had been given the opportunities as a youth, then my life might have been turned out different. That I actually could have become something other than what I did.

Leon (Swaleside, forties, mid)

A few men who ‘trod water’ were less inward in their focus; their accounts of marking time were more sociable, and the social group, not the self, was object of their ethical work. Some men at Swaleside cited their friendship groups as a reason not to progress too soon; in them, norms of reciprocity and conviviality prevailed, in contrast to the more competitive, mistrustful nature of life on the wings more generally:

Get the Xbox out, play FIFA… You can cook, sit down, have a talk with your friends and that […] We watch boxsets and stuff like that, music.

Ebo (Swaleside, twenties, mid)

To summarise: men who ‘trod water’ saw themselves as very much being ‘held’ by the prison. As Fergus McNeill (2009) notes of the term, to be ‘held’ entails a certain ambivalence. ‘Hurtful’ aspects of the sentence plan—particularly its demands for accountability and change—were kept distant: they recognised work to be done in relation to risk. But now was not the time. Treading water could involve finding ‘niches’ (Toch 1992/1977) of comfort and conviviality, or what Irwin (1987/1970) called ‘gleaning’.

6.4.3 ‘Drifting’

A third response to risk-related obligations was to ‘drift’. Like ‘treading water’, it involved no immediate engagement with the sentence plan. But it did not defer sentence plan goals, instead ignoring them. Found in every sentence stage, around three-quarters of ‘drifters’ were in either the early or post-tariff stages, with the latter usually very far over-tariff. Most also had complex risk profiles and occupied the ‘high risk’ bands summarised in Figure 6.1 (c). All except one had been convicted of intensely stigmatised offences. Often cynical and alienated, they saw risk management measures—and not merely the length of the sentence—as obtuse, entangling, and obstructive by design. While not denying their guilt, they typically felt that it obstructed what really mattered, and hence was morally thwarting. Out-and-out resistance was futile, and threatened formal progression. Thus, rather than engage with it, many simply followed their own priorities and hoped for the best.

Some complained that rehabilitative provision was not suited to their needs. William made this criticism in relation to a course, which (as he saw it) only scratched the surface of the reasons for his addiction:

I’d been to rehab a couple of times [before prison and] I’d already covered everything that they did on the course. And I’m not even too sure that the course really… That it would have given anyone anything. [It was trying to say], perhaps, “think more positive about what you can do instead of drugs” […] but I think it did seem a bit pointless at the time.

This was at [HMP X] , was it?

Yeah. Where I was happy. And I wasn’t using. And I didn’t feel I needed [heroin]. It probably would be more beneficial if I did it now, where I’m depressed, and I’ve been using.

William (Swaleside, forties, early)

Here, the sentence plan ‘hurt’ by prescribing ill-timed intervention on its own terms. Elsewhere, it ‘hurt’ by being too constraining. Timothy, whose RoSH assessments classified him as the highest-risk member in the entire sample, complained that “when [prison staff] look at me, they only look at me from the end of a cattle prod” (from interview notes). Applications for jobs and educational opportunities had been vetoed, and contact with some members of his family was forbidden. He resented all of this deeply:

The sentence plan doesn’t even reflect what this prison wants from me, not at all. It’s 95% interested in what I did in the past, 5% on how they want me to behave now, and nothing at all on what I should do in the future. Why plan the future retrospectively? Why face backwards if you’re going forwards?

Timothy (Swaleside, twenties, very early), from interview notes

Compliance with the sentence plan, for these men, seemed to offer no amelioration of an intolerable situation. ‘Drifters’ lacked ‘institutional hope’ (Seeds 2022); they were ‘held’ not in the sense of being worked on, but of being pinned down. The moral message they heard was both, “you are risky” and, “you cannot change this”. Interventions felt, perplexingly, legitimate in principle but ineffective in practice. They were hardly worth engaging with:

Oh, courses can only be for good […] But I’ve never been [offered the chance] […] My fear […] is that they will still want them, whether they think they work or not […] I look at people who’ve passed, gone on to C-cats […] I’m really appalled at their behavioural tendencies, their lack of control […] there’s no rehabilitative factor or improvement, as I see it.

Gerald (Swaleside, seventies, mid)

Just under half of ‘drifters’ were well over-tariff, in every case by more than a decade. They all accepted their guilt, and had all been subject to intensive interventions which some had found meaningful and helpful. But a principle of diminishing returns was evident:

I know that there’s at least thirty [courses] that I’ve done […] But […] it just fucking goes in one ear and out the other now.

Do you mean you [no longer] engage with them seriously?

Yeah, exactly.

Chris (Swaleside, sixties, post-tariff)

Again, here, a sense of thwartedness is evident: unable to influence the constraints they were under, risk controls ‘hurt’ these men. They were ‘held’ in prison but to protect others from them, not to secure improvements for themselves. Some were angered that earlier reformative efforts had not resulted in their release. Risk assessments felt like harsh judgements:

I hate parole boards. What they do is… they’re just digging in the shit that I planted roses in years ago, if you know what I mean. They still want to see shit. And it’s gone […] I’ve even sat on the parole board and said, “you know what, I couldn’t give a flying fuck if you let me out or not. I’m free inside. You don’t understand that.”

Fred (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

Fred’s words convey exasperation. He, and others like him, feared that their futures would be permanently compromised by their pasts, that what they did in prison would make no difference, despite what were often strong internal narratives of remorse and repentance. Risk management measures were ‘hurtful’, not because these men insisted they had always been good, but because they had become better, and were not recognised as such:

Psychology called me in about three or four years ago […] and said to me, “Can you give me a hypothetical situation where you are likely to reoffend?” I said to her, “Do you possibly think for one minute I entertain [the idea]? That’s not going to happen […] I have got absolutely no thought of or intention of ever putting myself in a situation where I am likely to offend. Where on earth are you coming from?” […] That was the end of that interview. I think it lasted two minutes.

Derek (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

Disengaging from official accounts of ‘the good’ meant that many searched for alternatives. Some (like Fred’s account of being ‘free inside’) were metaphysical. Others cultivated forms of goodness beyond the scope of risk assessment, and accessible in the here and now:

What matters to you, if not ‘jumping through hoops’?

[Gesturing outside the wing, towards the gardens area] Digging beds over there. And weeding beds over there. And turning compost over there […] [I’ve been at it for] eighteen months. There was no beds there when I went over there. It was all turf […] I don’t go on the classrooms any more […] That’s what I’m doing here, is digging. All the time.

Chris (Swaleside, sixties, post-tariff)

These ethical projects, and the futures they looked towards, were fundamentally private: the wider goods (e.g. public safety, public protection) which risk practitioners sought to secure were seen as intrusive, unjustified, invasions of this privacy:

[My licence] says not to have contact with children under the age of sixteen, yes? Well, I’m not in for a charge like that, for children. I never have been. And [yet] that’s one of my conditions. Well, they said that last time at the parole board, “Well, he’s not in for any offenses against children. So, this should be taken off” […] So [it was,] and obviously now, it’s back in this parole dossier, and I’m not happy about it […] I can’t see the reason behind it.

Jeff (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

The fundamental assertion here was one relating to ethical autonomy: the right to be recognised for the capacity to govern one’s own life, rather than being obligated to govern oneself in others’ interests:

Whatever I do, whether it be getting a smart phone, whether it be having contraband or refusing to do something that officers are telling me, my motives or my reasoning behind it is almost… Like, there is a method to my madness […] I think there has always been some sort of ethical thinking to what I’m doing or understandable reasoning why I’m doing something.

Simeon (Swaleside, twenties, late)

Yet autonomy like Simeon’s often broke rules. Men who ‘drifted’ were not progressing. They considered themselves capable of (and were more interested in) forming their own ethical projects; when this kind of behaviour came to the prison’s attention, it seemed risky and non-compliant.

To summarise: those who ‘drifted’ followed their own moral ‘maps’, and behaved autonomously without performing compliance. They wanted changes they had made in prison to wipe clean the stain of the offence, and risk interventions ‘hurt’ them by refracting them through a lens. They perceived misrecognition in this, and no ‘help’. As a result, they mostly followed private conceptions of the good, which failed to pay the requisite lip service to the prison’s disciplinary authority. In not consenting to occupy a subordinate ethics, they were usually not, in fact, going where they said they wanted to go, but were instead ‘drifting’ and hoping for the best.

6.4.4 ‘Swimming onwards’

A final response to risk management was to ‘swim onwards’. Participants who did were nearly all in the late and post-tariff stages,17 and most were at Leyhill. Those at Swaleside had arrived recently, having ‘come unstuck’ following long spells ‘treading water’ and ‘drifting’ in maximum-security prisons. Now, they believed themselves to be, if not ‘on a roll’, then at least carrying momentum. They had something to look forward to, and their actions were bringing it within reach:

I’d like to think the prison is invested in me. Maybe not on a personal level per se […] but I think the system is invested in people that want to help themselves […] I feel, since I’ve been here especially, they’re helping me to get out of the door, pushing me in that direction.

Daniel (Leyhill, fifties, late)

Daniel’s reference to reciprocation was significant: these men were confident that ethical behaviour (as they understood it) would both be good in its own right and secure progression. Risk constraints ‘held’ them in prison, but they were willing to think this ‘holding’ might benefit them.

Their offences and risk profiles varied. About half had been convicted of confrontation/fight murders, about half intensely stigmatised murders, and one an intimate partner murder. Accordingly, they had experienced many kinds of intervention. What most clearly distinguished them was an acceptance of legal guilt and a tendency to acknowledge a legitimate public interest in risk management, even where it frustrated their own. In short, they treated the offence not simply as a private wrong, but as a public one. This did not entail endorsement of every constraint, but they saw these holistically, within a wider legitimising frame. They complied, rather than resisting or claiming to know better:

When you say you’re not really a ‘medium’ risk, do you mean they’re kind of typecasting you?

Yeah. But I understand the reasons why they’re doing that.

Right. So you’re kind of accepting it?

Of course. Of course. Because their job is to protect the public […] And… if there’s a risk, or an increased risk… in other words, if I got into a relationship, then yeah, there’s a bloody increased risk. Course there is. And I understand where they’re coming from. And I respect that. But it doesn’t mean I want to get in a relationship. ’Cos I don’t.

Grant (Leyhill, fifties, late)

They ‘wore’ the ‘risky’ label for practical purposes, whether they accepted its substantive truth or not. In this, they differed from those who ‘trod water’ (because they were not waiting to engage but engaging now), and from the ‘drifting’ and ‘resisting’ groups (in that they considered risk management measures as having legitimate aims, regardless of how they personally were impacted). This sense of legitimacy helped them not to strain against measures which did not always closely conform to their own understanding of who they were and what they might do.

A few had lengthy experience of intensive therapeutic interventions. For them, the internalisation of risk represented a long tutelage. Their narratives about the offence and about changes undergone in prison seemed to be both sincere and endogenous, and instrumental and imposed. Engagement with therapy had yielded personally important results: long-awaited progressive moves, for instance, or the relief of unbearable shame through renarration, or a way of handling the flood of highly destructive emotions which characterised the early sentence stages:

I was on constant watch18 cos my head was all messed up. I was a sick man […] The only thing what sorted me out was therapy.

Phil (Leyhill, fifties, late)

I was at rock bottom for probably about five years. I was fighting back, fighting against everything […] Assaulting staff… I threw an officer down a flight of stairs, tried to bite another one’s fingers off. So they put me on the book.19 […] It sort of carried on […] I knocked a screw out in the showers and we had a big fucking riot. I was in the block for three months. Then I went to [another dispersal prison] and that’s where I really started to dig in and accept what I was in prison for, accept the sentence, accept my guilt, accept everything around me.

Tony (Swaleside, forties, mid), from notes

Risk interventions relieved travails such as these: not merely an outside imposition calling for an insincere performance, nor a block on progression, they became a ‘technology of the self’ (Foucault 1988; see also Faubion 2011). They allowed past behaviour to be rejected, redescribed, and reframed, but without threatening personal disintegration. More intensive interventions tended to offer credence to, and foster narrative support for, the notion that deeply harmful behaviour arose from deep distress. The resulting narratives situated the speaker (and the offence) in a longer story, acknowledging their responsibility (and capacity) for harm, but also drawing attention to past victimisation. This was ‘helpful’ in that it produced a sense of reward:

See, for me it’s that understanding and it’s that knowledge […] It’s the skills that you need to understand yourself. You can only do that yourself […] I never knew anything about DSPD.20 Once I got there and I started to learn about what it was, that’s when I wanted to be there. I wanted that change. I wanted to put that effort in […] If you open up and allow yourself to be so red and raw with your emotions, with your thoughts, then you’re going to gain out of it.

Nicholas (Leyhill, thirties, post-tariff)

This account is particularly illuminating. Prisoners throughout the entire sample emphasised their autonomy and agency. So many insisted, “prison doesn’t change you, you change yourself”, that the phrase felt clichéd. In one sense, Nicholas’s attitude was no different from those of participants who ‘drifted’, ‘resisted’ or ‘trod water’, and hence were following their own ethical priorities. What distinguished him, and others in the ‘swimming onwards’ group, was his acceptance of the basic terms on which risk discourse invited him to narrate his life: by acknowledging the persistence of risk, and the necessity of ongoing constraint. Nicholas at first “never knew anything about” DSPD, and it is telling that only “once [he] got there” did he find that he “wanted to be there”. What facilitated his willingness to work towards ‘transformative risk subjectivity’ (Hannah-Moffat 2005) was a more complex narrative of personhood than he had previously been able to offer. It emphasised emotionality and the development of coping skills, and communicated a fundamentally care-laden message: that his distress was worth relieving. His account—which articulated his conviction by reference to his childhood victimisations—was co-produced. It was an artefact of intervention, but one which relieved suffering (in his case, relating to shame).

Other men offered similar tales. Intervention with these care-infused qualities, even when it arrived very late in the sentence, generated reciprocal compliance. Those who felt intense guilt or shame relating to the offence could make peace with what they had done. They ceded a certain degree of narrative autonomy, inhabiting (rather than merely performing) the role of a risky subject. Renarrating an entire life as a prelude to the offence emphasised continuities between past, present, and future, ruling out the possibility that it could have been an aberration. The implication was that, at least at the time, they could not have done otherwise, and therefore did not possess ‘true’ moral autonomy:

I think it was inevitable that something was going to eventually happen. [And if] I wasn’t caught […] then it is more than likely something else would have happened, and it is more than likely that it would have continued […] How far it would have gone, I don’t know […] [but] that behaviour wouldn’t have just ended of its own accord.

Nicholas (Leyhill, thirties, post-tariff)

Facts, realisation, you know? […] What I was like, what I am, who I am, what I’m capable of. They’re just basic facts now, and I have to accept that […] I can change myself, I can behave like a different person, I can become a different thing, a different way of thinking about life and that. But it doesn’t change the facts.

Billy (Swaleside, forties, late)

It followed, of course, that if persistent risk required ongoing management, then the constraints of the life licence—and not merely the penalty phase of the sentence—were legitimate aspects of punishment. One result was that frustrations with risk management—the sense that it impeded them or thwarted a ‘good life’—were less widespread in this group than in others. Indeed, on some level, risk management was the precondition for a good life.