4 Becoming ‘a murderer’

How does a murder conviction shape the ethical self?

This chapter contributes to recent research on the place of the index offence in ethical reflection by men convicted of murder, by adding nuance to that research. Recent studies of long-term and life imprisonment have taken an interest in how a conviction and sanction for a serious offence, generates a striking form of ethical reflexivity, which, it has been argued, drives adaptations to the sentence. The chapter’s central argument is that this focus in recent research has been imprecise in its descriptive approach to the offence of murder. Building on other works which have increasingly sought to consider moral communication and retributive theory using empirical evidence about prisoners’ moral thinking, the chapter’s main methodological contribution is to use an existing murder typology to structure its analysis of prisoner accounts of the offence, whereas other studies of long-term imprisonment have tended to use ad hoc inductive typologies, or instead to treat broad legal categories of offence as though they were a single undifferentiated kind of act. The resulting analysis generates a description of moral thinking by men convicted of murder, differentiated by offence type. It identifies different styles of moral reasoning among the different offence type groups, but also identifies some cross-cutting factors which, regardless of offence type, seemed to lead to variations in feelings of guilt and shame.

murder, identity, sociology of punishment, moral reflection, england and wales, life imprisonment

[M]urder is, like many ‘social facts’, not necessarily easily defined or understood […] Although virtually always a major crime […] most, if not all, societies appear to have a moral hierarchy of murder, both with reference to its victims and its perpetrators. [Even if] all killing is proscribed, particular forms are given harsher punishments than others.

Morrall (2006 pp. 43–44)

Both penologists (Crewe et al. 2020; Herbert 2019; Irwin 2009; Leigey 2015) and forensic clinicians (Adshead et al. 2015, 2018; Ferrito et al. 2012) have been struck by ethical reflexivity among those convicted of serious violence, especially murder. Many lifers, it appears, “recognise the moral harm of [their] actions and build a new life in response” (Herbert 2019 p. 13). Some have also linked this with the passage of time during a long sentence (Crewe et al. 2020), and others have theorised a more general acceptance that blame was deserved, and punishment legitimate:

…[w]hen an offender acknowledges responsibility, they are accepting of their offender identity [though] they may also need to redefine and ‘discover’ a new identity.

Ferrito et al. (2012 p. 328)

These recent findings are somewhat at odds with findings from homicide research (discussed further in Section 4.1.2) that, despite the seriousness of the crime, those convicted tend to minimise and contextualise blame.

This chapter examines the space between the two. Its argument is that recent research has overplayed how consistent the ethical consequences of murder are for those held accountable. It makes the argument through comparisons: I subdivide the sample by murder type (using existing legal and empirical evidence to generate the subdivisions), and then describe how participants in these subdivisions were affected by the conviction and sanction. Where Crewe et al. (2020 p. 137) found that a “great majority” of their sample expressed “deep and ongoing remorse about […] their actions”, I note patterned variation in how participants negotiated with censure, and not consistent expressions of remorse.1

4.1 Disaggregating a diverse offence

To ground the analysis, the next two subsections address censure: what generates it, who receives it, and what they are typically censured for. One reviews how the law constructs the ‘seriousness’ of murders; the second reviews empirical evidence on the people typically associated with specific murder types.

4.1.1 ‘Seriousness’ in sentencing law

Schedule 21 of the 2003 Criminal Justice Act (UK Parliament 2003 sec. 321) specifies how the ‘seriousness’ of murders is to be converted into the penalty of imprisonment. Its impact on retributive severity has been noted (e.g. Crewe et al. 2020 Chapter 1; Independent Commission into the Experience of Victims and Long-Term Prisoners 2022 pp. 19–23; Mitchell and Roberts 2012 Chapter 3) but, though penalties grew, the mitigating and aggravating factors influencing a determination of ‘seriousness’ were mostly unchanged.2 They can be classified (barring a few outliers) into four loose groups, summarised by Table 4.1:

| Factor | Aggravation examples | Mitigation examples |

|---|---|---|

| The offender’s motives and intentions in the wider ‘homicide situation’ |

|

|

| The victim’s identity and conduct, usually in relation to vulnerability and power disparities with the offender |

|

|

| The nature of the violence used (e.g. cruel, gratuitous, premeditated, or excessive, esp. if victim(s) suffer intensely) |

|

|

| Weapon use |

|

None |

Several points emerge from Table 4.1. First, ‘seriousness’ relies in part on inferences about intent (see rows 1 and 3). As philosophers have argued (e.g. Anscombe 2000/1957; Cobb 1994; Schwenkler 2019) intent is a complex matter: socially constructed, and thus liable to be perceived differently by the law and by individuals. There is potential for assessments of culpability and ‘seriousness’ to diverge.

Second, ‘seriousness’ also depends on the identity and actions of victims (row 2). Empirical studies (e.g. Luckenbill 1977; Miethe et al. 2004; Wolfgang 2016/1958) find that victims, in some forms of homicide, may be “direct, positive precipitator[s] in the crime” (Wolfgang 1958 p. 2). Later scholars (e.g. Timmer and Norman 1984) increasingly rejected the victim-blaming implicit in this finding, without dispelling the underlying impression that some homicide victims are more ‘ideal’ (i.e. weaker, smaller, and attacked by a ‘big, bad’ offender—see Christie 1986); whereas others are active participants in a conflict leading to their demise. It is notable, therefore, that most of the aggravating and mitigating factors relating to victims in Schedule 21 position the offender as more powerful and the victim as weaker. There is aggravation if this is so, but no mitigation if (for instance) the victim provoked the offender, or if the offender acted in fear (rather than in self-defence).

The basis of ‘seriousness’ as seen in rows 3 and 4 of Table 4.1 is more objective, resting on (for example) whether someone carried a knife or what violence they used. Yet the ‘excessiveness’ or ‘cruelty’ of violence (for example) is a matter for interpretation, especially where people act under deranging influences such as extreme emotion, mental illness, or substance abuse. Moreover, aggravations based on weapon use (row 4) are arguably deterrent more than retributive, in that they ‘make an example’ of the offender, whose reasons for acting as they did are treated as irrelevant. While unquestionably illegal and dangerous, carrying a weapon might appear rational under some constrained circumstances, such as when people are engaged in activities like drug dealing, or when they perceive a risk of violence against them and do not trust that it will be prevented. The point is not to justify weapon-carrying, but to point out that its ordinariness and fathomability are highly contingent on context.

To sum up: censure in Schedule 21 derives largely from an observer’s inferences, suppositions, and cultural beliefs in applying the aggravating and mitigating factors; that is, on their beliefs about what could have been ‘going on’ in a homicide situation. The law discards or ignores information which participants in it might consider essential to a fair evaluation. The result is to open space in which blame may be disputed.

Because the law does not make clear and consistent distinctions between cases, it is to empirical typologies that we must turn for the classification to be applied in this analysis.

4.1.2 ‘Murder types’ in empirical typologies

As Chapter 2.2.2 showed, the incidence of murder is patterned on other variables. Murder typologies do not agree on how to classify homicide events (Skott 2019 p. 4), and take diverse approaches to the task.4 Most typically, typologies

…emplo[y] rudimentary categories such as age, sex and ethnicity of victims and offenders as well as geographic locations where homicides occurred. While such information is essential for comparing rates of homicide, it is basically a list of attributes […] [which does not] examine more closely what happens in murder events and why they might have occurred.

Dobash and Dobash (2020 p. 26)

Classifications based on ‘murder events’ (or ‘homicide situations’) offer a more useful basis for the analytical comparisons attempted here. They classify using data on participants and an account—a sequential causal narrative of the offence. One, by Russell and Rebecca Dobash (2015; 2020), was developed from case records and interview data in a British sample of 866 cases. It takes the victim’s gender as the most fundamental structuring variable, then subdivides cases by features of the ‘murder event’. Only major categories from the original set are used to subdivide cases in this chapter—subtypes were ignored, along with major categories not represented in the present sample. Thus the present sample is subdivided into four ‘murder types’ for analytical purposes: first, confrontation/fight murders; second, money/financial gain murders; third, intimate partner murders; and fourth, intensely stigmatised murders. The final item comes not from the Dobashes’ original classification, but gathers three of theirs and adds another they do not cover, as follows:

- sexual murders of women (2015 pt. II);

- murders of victims aged over sixty-five, whether

- women (2015 pt. III); or

- men (2020 Chapter 6); and

- murders of infants.

The following paragraphs sketch the main features of four ‘murder types’ in turn.

4.1.2.1 Confrontation/fight murders

‘Confrontation/fight’ murders (Dobash and Dobash 2020 p. 39) are “linked to disputes involving the personal character and identity of perpetrators who […] view fighting as a means of obtaining respect and/or enhancing their reputation.” Often, the violence involved is performative: finding it intolerable to let a perceived slight pass unavenged, those involved imagine violence to be retaliatory, even when the slight is trivial. Confrontation murders commonly occur in public places, with multiple perpetrators, witnesses, and bystanders. They can appear sudden and spontaneous, but the antecedent disputes need not be: offenders and victims are acquainted in around three-fifths of cases. In the Dobashes’ sample, those convicted are young (average age 27), tend to be working-class, are unemployed, or work in unskilled manual occupations.5

4.1.2.2 Money/financial gain murders

Financial gain murders, meanwhile, share some features in common with those in the ‘confrontation’ group: working-class, unemployed principals, averaging age 27, who tend not to act alone (67% of cases) (2020 pp. 75–77). They are more often committed against strangers (2020 p. 102), but otherwise, the underlying relationships and situations are heterogeneous. The Dobashes (2020 Chapter 3) and others (e.g. Miethe and Drass 1999) caution against a sharp division between ‘instrumental’ and ‘emotional’ violence, one making confrontation murders ‘expressive’ while financial gain murders are ‘calculated’. Instead, they argue, heightened emotional and physiological states are common to both, though the motivation to obtain “money, resources or commodities” and the higher degree of preparation (with weapons brought to the scene in 90% of cases—see Dobash and Dobash 2020 pp. 75–77) can make financial gain murders appear more deliberate, and hence more culpable.

4.1.2.3 Intimate partner murders

Intimate partner murders are analytically and aetiologically distinct from the previous two. Victims can include female partners, but sometimes also their children, family members, new partners, or friends, cases the Dobashes refer to as ‘collateral’. This is a gendered, hidden, and specialised form of violence (2015 pp. 47–9), typically occurring in private settings such as the home. Though it is often extreme (2015 pp. 51–57), men who kill women tend not to identify with it, and often deny their capacity for it (2015 p. 67). There is typically a pattern of escalation, with earlier violence against the victim or against previous partners; Dobash and Dobash (2015 p. 39 and, more generally, pp. 40-47) link this to emotions of “possessiveness, jealousy, and infidelity […] These are acts in which men attempt to possess women and ‘keep’ them and may be followed by acts of revenge when possession, control, and authority are lost.” Intimate partner murderers are less likely to have been socially and economically marginal than with other forms of murder, and they are also usually older at conviction—around 40, on average (2015 p. 40).

4.1.2.4 Intensely stigmatised murders

Finally, three further murder types present in this sample and described by the Dobashes are grouped together as intensely stigmatised murders. Across the Dobashes’ underlying categories, those responsible are typically young, highly socially marginal men, often acquainted with their victims but not close to them. Troubles at school, early alcohol abuse, early-onset offending, early experiences of institutionalisation, and (in some cases) physical and/or sexual abuse or neglect commonly featured in their histories (2015 pp. 153–186, 221–41). Usually unemployed as adults, many misused alcohol, or drugs, were persistent offenders, and had no (or a violent) history with former partners. These offences were almost always committed alone in the victim’s home or a secluded public location. In prison, these men were highly likely to be shunned by others, and to be assessed as dangerous by prison staff, and commonly denied either the murder, a sexual offence relating to it, or both (2015 pp. 172–182, 235–237).

4.2 Index offences in the sample

Having described the categories used to structure the analysis, the chapter now describes the sample in these terms.

| Murder type | Participants | Age at conviction (avg.) | Tariff (median, yrs.) | Time served (median, yrs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confrontation/ fight | 20 | 28 | 15.5 | 10 |

| Intimate partner | 12 | 41 | 19.5 | 7 |

| Money/financial gain | 6 | 27 | 19 | 11.5 |

| Intensely stigmatised | 10 | 24 | 16 | 19.5 |

| All | 48 | 30 | 17 | 10.5 |

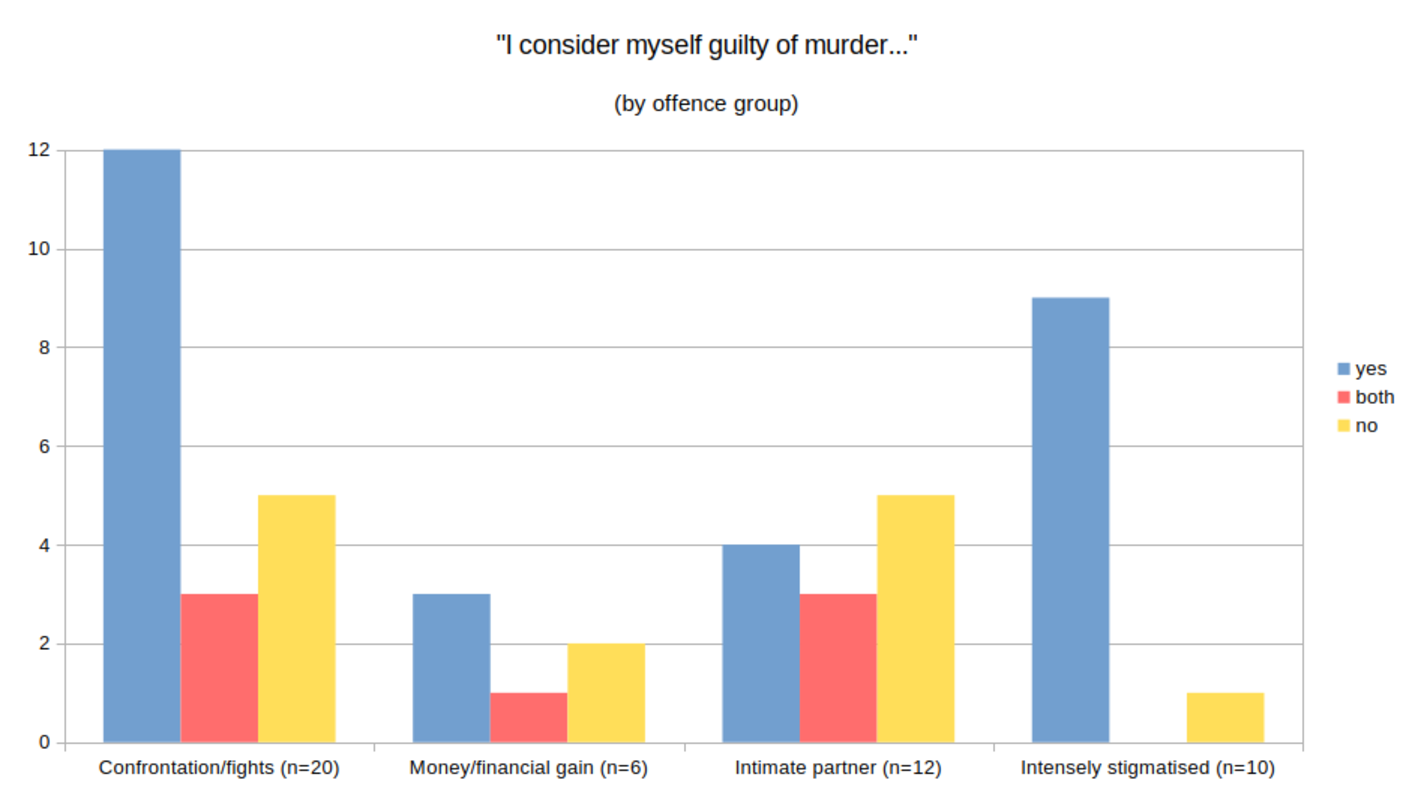

It shows descriptive statistics on their ages and sentences (4.1 (a)), and their evaluations of their own guilt (4.1 (b)),6 both subdivided by offence type. It is noteworthy that neither unambiguous expressions of guilt nor more severe sentences were evenly distributed, with the ‘intimate partner’ group serving the heaviest sentences, and the ‘intensely stigmatised’ group most likely to admit their guilt.

4.2.1 Confrontation murders

Twenty participants (42% of the present sample) were in prison for ‘confrontation/fight’ murders. Eleven (55% of the group) were convicted with one or more co-defendants. All their victim(s) were male. Ethnically, they were heterogeneous: thirteen were White, nine were of Black or Mixed, and one of Asian, ethnicities. With very few exceptions, they fitted the Dobashes’ characterisation of this group: most were young when convicted (median age 27) and unemployed or intermittently employed. Many were accustomed to violence: twelve had served previous prison sentences, and six had at least two prior violence convictions. Two had previously faced homicide charges, though with neither previously convicted of murder. These were, then, mostly men willing to use violence and who saw in it a means to resolve disputes. Thirteen (or 65%) unequivocally admitted murder. Of the others, three equivocated, and five denied guilt, of which three were technical and two were strong claims of innocence.7

4.2.1.1 Slights, provocations, and co-offending

In accounts of the offence among this group, the victim often appeared as an active participant. Interviewees nearly all suggested that retaliation against a slight was justifiable in the abstract, even if they admitted with hindsight that a lethal outcome was excessive. The slights they described varied, but gradations of status and hierarchies of worth were in the background of most:

[Speaking rhetorically to his victim] I don’t BELIEVE you’ve done that to me.8 That’s what… That’s the truth, isn’t it? People don’t hit me. It doesn’t happen, in my world.

Robert (Swaleside, fifties, early)

Heightened emotions—especially anger—were a common theme. Gary’s shifts of tense in the following quote, and his slippage from first to third person, personified his anger as a force overwhelming his faculties of self-control:

I don’t know how we end up fighting, but somehow I must grab the knife […] And I stabbed him [several dozen] times9 […] all I can remember now, in my head, it kept saying—my anger—“don’t let him get away with it” […] For some reason, it could not let it drop […] Red mist, they call it.

Gary (Swaleside, fifties, early)

William’s offence escalated around a drug debt he owed to his victim, but their relationship was multifaceted. His account of it vividly suggested fear, an emotion which, like anger, was prominent in these accounts:

I genuinely felt it was either me or him […] No matter what the judge said, I know. I know what happened […] I’d understand manslaughter, but […] [I wish the court could have seen] [w]hat kind of a person he was. How intimidating he was, and how… how I, personally, felt… and how I could be intimidated and… so, how I was scared, how scared I can be […] And how much of a horrible person he is. Or was.

William (Swaleside, forties, early)

Other narratives echoed William’s “me or him”, suggesting contingency in who survived and who died. Victim and perpetrator appeared morally interchangeable, prompting frustration for participants who felt wrongly blamed as aggressors:

Some people I interview tell me, “When I started the sentence I knew I had to change,” or, “I knew I wanted to change,” or something. It doesn’t sound like that’s your–

[angrily] Change from WHAT? Listen, I was in my house, mate […] You get what I’m saying? He came to my house. He was threatening me. It happened at the front of my doorstep. [If] they’d given me manslaughter, then maybe.

Courtney (Swaleside, forties, late)

Anger or fear; provocation or intimidation; the presence of strong emotion diluted feelings of responsibility. So, too, could the involvement of multiple co-defendants:

From [more than five] assailants in the CCTV footage, the police only identified and charged [some].10 [They were all] acquitted except him […] [Today] he would choose to plead guilty to manslaughter to get out of prison sooner, but he was not guilty of murder because he hadn’t stabbed anyone. Said the police “got away with doing whatever they wanted”.

Yakubu (Swaleside, thirties, early), from notes

These were not denials of responsibility, exactly: as noted in Section 4.2, nearly two-thirds of the group expressed unequivocal guilt when asked a yes/no question. It was more that their narratives spread blame: by sharing it with the victim, or with co-defendants. Expressions of regret were not uncommon, but usually centred on parties other than the victim, particularly family members (of both participants and the victim).

As Courtney (quoted above) said most directly, even when they admitted they had taken life, this group did not always feel obligated to change; enduring the punishment seemed enough. Correspondingly, when they acknowledged that they had changed in prison (as was inevitable considering the spans of time involved), they seldom attributed this to the sentence, but used terms like ‘growing up’ or ‘maturing’. Some were ambivalent about sentence progression, lest projects of self-preservation and survival be mistaken for an admission of guilt, or co-opted by the prison as evidence of its reformative success:

I ain’t changed who I am. You understand what I’m saying? So, you ain’t rehabilitating shit […]

Is that what you meant when you said it felt odd to get your C-cat?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. It pissed me off because, obviously, it’s a great thing to have. But it’s, “hold on, does people really think I’m doing this fucking bird?”11 […] Like, I’m not TRYING… I’m not HAPPY to get a C-cat […]

You don’t want a pat on the back, you mean?

Yeah. Why am I happy about a C-cat? I shouldn’t even be in jail.

Reuben (Swaleside, thirties, mid)

This subsection has reviewed how slights, provocations and co-offending—all of which are common in confrontation murders—affected feelings of responsibility. These men tended to accept they had lost control of themselves, but did not necessarily accept that this was their responsibility, rather than someone else’s. The next subsection briefly examines one kind of confrontation/fight offence which produced deeper feelings of remorse.

4.2.1.2 Acquaintance with the victim: friends, acquaintances and strangers

Some participants convicted of confrontation/fight murders had killed someone they either cared about, or recognised they ought to have done. Expressions of remorse and regret centred on the victim were more the norm here. It was evident that such acts could be judged harshly in prison:

[My friend] said, “He was your best mate, Bill. How could you kill your best mate?” […] He was deliberately making me realise what I’d done […] I needed somebody to say, “Fucking hell, Billy, that was fucking bad, that”—to actually put it in context.

Billy (Swaleside, forties, late)

With known victims, there was also greater awareness of who else had been harmed, via ripple effects:

I’ve just took away their brother, their uncle, their… well, not their son, the parents are gone, but do you know what I’m saying? […] I wouldn’t tell them [in court] what he done [to provoke me] because, come on, that’s not fair, is it? So, I said, “I’m not saying anything,” just to show a bit of respect […] He weren’t a stranger, he was someone I grew up with.

Ron (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

My daughter, my youngest daughter, and my mate’s daughter—the [mate] who I killed—they was out shopping that day […] They were best friends […] [My family] had to move house, the kids move school, everything.

Terry (Swaleside, fifties, mid)

Thus grief and guilt magnified one another, and tightened censure’s grip. Participants had harmed real, concrete people, rather than simply transgressing abstract legal/moral principles.

4.2.1.3 Ethical work—attitudes to confrontation

Those who had killed friends aside, men convicted of Confrontation/fight murders expressed regrets centring not on their victims, but on the damage to themselves and their loved ones caused by their propensity for violence. Since prison life abounded with provocations, slights, and fear, and also with opportunities for reflection, there was scope for them to reconsider how these stimuli—which were also those that produced the offence—affected them.

Thus, despite feeling a dilute form of responsibility, many of these men described shifts in their attitudes to violence. A kind of relational strategising drove this process. It involved neither a profound shift in moral attitudes, nor a reorientation towards interdependence, but instead a more calculating, self-distanced mode of being in the world, best characterised by self-control and the practical wisdom of ‘choosing battles’.

To describe this shift in greater detail: some early-sentence prisoners described provocations as something to be courted. Establishing a reputation for violence offered power, of sorts: to intimidate others, and to extract concessions from Swaleside, a prison trying to reduce violence rates. For Levi, prison life reproduced the moral logic of street violence; reputation was a means to an end. Thus in his case, ethical work involved acculturating himself to segregation, which from his vantage point seemed the only (and a very short-term) consequence of prison violence:

I can get a move [off the wing if I want one]: I can go on the wing, right now, knock out a screw and get moved off the wing [kisses his teeth]. There’s no difference. I ain’t getting no extra days… Block’s my second home.12

Levi (Swaleside, twenties, very early)

Participants later in the sentence, however, mostly understood the ‘power of the pen’ (Crewe 2009). They cared to keep a clean record more than Levi did, and some were also fearful of prison violence. For them, provocations and confrontations were to be avoided at any cost:

[Anything I do outside of my cell, I do] just to get some money, so I can have vapes and treats […] [My cell is] my rock. It’s the one place where I can relax, where I don’t have to think about anything […] The door’s shut, there’s going to be no aggro, no trouble on the wing, nobody messing me around.

Billy (Swaleside, forties, late)

Others handled provocations not through disengagement, but via judicious engagement. Understanding one’s own limits and social dynamics on the wing became the ethical priority. Many participants described themselves as astute judges of character, and prison as the whetstone on which this faculty was honed:

I’m observant now, more than I’ve ever been […] I suppose I’m just watching everyone. Thinking, oh, he’s being a bit of a prat today. You know, over an orange, or over a Penguin or something stupid. People getting stabbed for it.

Gary (Swaleside, fifties, early)

Minor debts served as a test of relationships and of one’s own reactivity, with several men describing borrowing and lending as a deliberate test of character:

It’s who you let in. So obviously, I give people one chance […] I will borrow you a bag of rice and then if you don’t pay it back then I would be like, aight, cool. I’m not even gonna run you down for that rice, but I’m not gonna borrow you rice again […] I’ll give you one chance.

Reuben (Swaleside, thirties, mid)

A bag of rice was self-evidently worth less than sentence time added through being classified as risky prison violence. Iterated, such insights could produce deeper transformations: shifting attitudes to the importance of ‘face’, ‘reputation’, and provocation itself. An ethics initially responsive to incentives, which dealt in cost-benefit calculations, sometimes provoked further-reaching examinations of the beliefs underlying participants’ emotionality. This was real change, but did not necessarily involve “deep remorse” centred on harms done to the victim. It could foster a sense of autonomy and self-respect, won through growing self-control and (perhaps) self-mastery. It was telling that many in this group were particularly committed to their health, following strict regimens of physical training, and habitual routines building self-discipline and self-esteem.

About half six… get up, tidy my bed up, the usual stuff […] These are like rituals I do every morning. If I don’t get up and drag myself out of bed and I don’t do the tidy, I know that depression’s kicking in […] Then I come out, go to the gym, train as hard as I can […]

What does it mean to you, the gym?

Oh, it’s everything. That’s my medication, that’s what keeps me… […] [When] I come to prison I was fucking… […] I’ll have to show you a picture, I was a big fat fucker. I was always slim and athletic as a boy, but in my twenties [I got] lazy, with drinking and eating and whatnot. Since I come to prison I’ve trained practically every day.

Tony (Swaleside, thirties, mid), from notes

4.2.1.4 Summary—confrontation/fight murders

To summarise: men convicted of Confrontation/Fight murders typically entered prison seeing violence as normal and rational, if also context-specific. They were used to it. Some sought opportunities to demonstrate what happened to anyone who ‘mugged them off’; others were fearful of victimisation by others, and sought pre-emption. Most, though, identified with violence to some extent, and did not find it difficult to think of themselves as (formerly) violent men. Most also admitted at least some involvement in causing someone else’s death. But their offences, often not committed alone, felt less blameworthy than the hefty ‘murder’ tag often implied.13

In prison, few had relinquished the general feeling that they had been provoked. Nonetheless, unless they maintained innocence, or were very early in the sentence, they were not unregretful, and their thinking about the costs and benefits of violence had shifted. They ‘turned around’ or ‘turned away’ from their past actions—consistent with repentance as defined by Bottoms (2019 pp. 129–136)—but were unrepentant in the ‘deep’ sense advanced by Duff (2003), which involves a broad, heartfelt commitment to projects of reform and reconciliation. They commonly expressed feelings of regret and remorse, but only for those who had killed someone they cared about were these centred closely on the victim.

In most cases, then, these men responded to a message of deterrence, not to one demanding reform. In prison, they increasingly tried to avoid provocation by keeping their emotions at arm’s length. This was not easy, but as an environment, Swaleside at least afforded many situations to test their resolve. Ethical change centred on beliefs about provocation, the value of reputation and ‘respect’, and the costs and benefits of violence. It did not necessarily result in a far-reaching recognition of human interdependency, nor in profound moral realignment.

4.2.2 Financial gain murders

Six men (13% of the sample) were convicted of financial gain murders. Their victims included one woman and six men. Like the Confrontation/Fight group, their median age at conviction was twenty-seven. Two maintained a technical claim of innocence;14 one equivocated; three admitted guilt. Four had prior convictions, and three of these were serving at least their third prison sentence. Their median tariff was 19 years. None of these men had acted alone. In most cases, co-defendants been part of the underlying conspiracy (to rob or burgle), but had usually not been charged with murder.

4.2.2.1 Panic and (mis)calculation

Again, the emotional content of offence narratives in this group was striking. Most spoke in ways not suggesting ‘calculation’ or ‘instrumental’ thinking, but intense agitation: neither shame nor possessiveness nor jealousy nor anger (as with other groups), but panic, whether prompted by the offence situation itself, or some wider circumstance. Commonly, they had lost control of situations they believed they could handle:

As soon as they were in the house he remembers thinking, “I’m miles out of my depth here”. [The victim] started screaming to raise the alarm. He panicked, and [tried to silence them] […] He learned later that [they] had died […] He never meant harm, but said, “that’s not the point, is it?” […] He found the tariff shocking but accepted it quickly: “right from the day” of the offence he knew […] it was wrong, and he’d pay a heavy price.

Liam (Swaleside, forties, mid), from notes

Ebo, similarly, had not expected the target of a robbery to resist:

I got a knife in my hand… the guy… He was sixteen stone, I must have been about ten stone, eleven stone… I’m not saying I’m a kid but I’m a young… a teenager… fighting a sixteen-stone man […] But I’m not saying… I’m not trying to say… I mean, I know I shouldn’t even have been there… I don’t know… I didn’t know… how to put across that my intentions were not to harm. I didn’t know how to do it then. I still probably don’t know. I probably still wouldn’t know how to explain about… There’s no way I can put it across to them.

Ebo (Swaleside, twenties, mid)

Ebo’s hesitations were revealing. His difficulty in “putting across” his lack of malign intent recognised that, on some level, the effort was futile: he “shouldn’t even have been there”. As both he and Liam recognised (Liam more explicitly), a fatal outcome rendered intentions moot: they had not been “carrying out any respectable project” and the people they were robbing “could not possibly be blamed for being” where they were (Christie 1986 p. 19). They were ‘ideal victims’, meaning that explanations (like Ebo’s) which centred on “victim-precipitation” (Wolfgang 1958) rebounded immediately on the narrator. Panic shifted responsibility—from one’s deliberate actions to one’s uncontrolled reactions. It made the offence appear less willed, and more a consequence of unwilled internal states.

In other accounts, things had still ‘got out of hand’. However, not panic, but more powerful forces beyond the individual’s control, were presented as having narrowed the scope for ethical choice. These forces could be internal—the insatiability of addiction, in one example—or external, as in the following case:

[Co-defendant] phoned him and said they owed [a six-figure sum] to the [organised crime financiers of their illegal activities]. They demanded repayment the following week. Threats were made: their creditors let it be known they knew where Frank’s family lived.

Frank (Swaleside, forties, post-tariff), from notes

This account suggested that Frank’s capacity to “act otherwise” had already passed (see Bottoms 2006 pp. 259–60). Situating his ‘loss of control’ temporally further from the murder, however, pushed Frank into a different kind of reflection: on his capacity for premeditation. Knowing he would be recognised by the victims of the robbery, Frank’s ability to actively suppress his own moral emotions had become, years later, the detail which troubled him the most:

I shot them in cold blood. That’s not nice, but it’s the truth. The only way you can do something like that is to dehumanise the person, see them as an object you need to move out of your way. Otherwise you won’t do it […] I thought about it in the car, all the way there […] I didn’t want to do it. I knew it was wrong. And I did it anyway. It took me years—years—to face up to it.

Frank (Swaleside, forties, post-tariff)

Like the confrontation group, these men pointed to the actions of others, or to relevant features of the surrounding context, to explain their violence. But it did not ‘work’ to share blame with the victims, because the implicit claim was paradoxical: the narrator had come prepared to use violence, but had not intended harm. Events had spun out of control, but these men recognised that this offered no justification: the wider situation was of their making.

In one case where the victim was less ‘ideal’, a theme of moral interchangeability was present, more reminiscent of the ‘him-or-me’ accounts described in Section 4.2.1.1:

All I wanted her [a risk assessor] to understand was that this guy was… You know, was the threat credible? […] The deceased had a firearm on him […] It’s not like man’s making up porkies. These guys was armed. We was armed. […] None of us didn’t have any qualms about shooting the other person. So it could have been easily him sitting here interviewing with you today […] Even though I was a bad person, the way that she was making it look… like, just, we went out just to kill this guy, do you understand? That wasn’t the case.

Leon (Swaleside, forties, mid)

Leon’s demand was that his offence be seen in context: conventional morality and the law offered no guidance in a ‘him-or-me’ situation. The risk assessor had challenged Leon’s insistence on this point, suggesting that he was presenting himself as a vigilante hero, and thereby minimising blame and evading responsibility. For Leon, this missed the point: no one emerged with credit from his account of the offence; both he and his victim were “bad people”, and his job was to make the best of having survived.

Generally, this group struggled to justify an unjustifiable situation, but wanted to describe the few, stark, choices they had perceived at the time. The killing was not the defining ethical moment in their accounts; it was a consequence of long-prior decisions—to become involved in crime, to use drugs, and so on. Only Frank, who had deliberately and calculatedly suppressed his moral emotions, described more intense feelings of remorse, suggesting that he saw the causes of his violence as internal, not external.

4.2.2.2 Moral difference and role-taking

No participant in this group had acted alone. Thus, as with the confrontation/fight group, the involvement of multiple actors was again significant, though it could intensify or lessen blame, depending on the circumstances. In two cases, official records made clear that a co-defendant had struck the fatal blow. These interviewees did not feel responsible:

I never intended to kill him, and I didn’t kill him, so I don’t lose any sleep over it. It’s a tragedy and I’m sorry that he’s died, but that was out of my control.

Dalton (Leyhill, thirties, mid)

Dalton, lacking previous convictions, found it difficult to rationalise the sentence as a form of cosmic justice for past misdeeds, as other joint enterprise defendants have done (Hulley et al. 2019). Nixon’s lengthier record of previous convictions offered more to work with in this respect, and his view of the sentence was more akin to cases described by Hulley et al., in which secondary parties constructed narratives in which they deserved punishment for something, even if not for the index offence, and by doing so made more sense of their predicament:

There’s a thing with me called swings and roundabouts. I’m doing this bird, and in the past, I’ve done a lot of stuff that I got away with, so this makes up for it […] Like, sort of, balancing the books, yes? […] [and then] I come out and live my life.

Nixon (Swaleside, forties, post-tariff)

Secondary parties, then, accepted no more than secondary roles, though sometimes invoked karma to make sense of their position. The other four men admitted guilt in the murder (one equivocally), but recognised that the lesser convictions handed down to co-defendants had been aggravated by the murder. Some felt responsible, and expressed guilt relating to the severity of sanctions received by others:

He basically had nothing to do with it […] with the planning […] He wasn’t active […] So in the robbery, he was just watching. He didn’t think what happened would happen.

Frank (Swaleside, forties, post-tariff)

One of my co-d[efendant]s, he was the lookout man. He had… not to say he had nothing to do with it, but he didn’t know nothing […] I feel it’s a bit harsh. He got manslaughter and conspiracy to rob. My actions shouldn’t have led him to be convicted to a manslaughter.

Ebo (Swaleside, twenties, mid)

With this group, then, unlike with the Confrontation/fight group, co-offending did not necessarily spread blame. It did lead, naturally, to moral comparisons, some centring on questions of desert and procedural justice, and some on roles in the homicide event. But expressions of remorse or regret centred, as with the Confrontation/Fight group, on how the sanction had impacted them and their loved ones.

4.2.2.3 Ethical work—taking responsibility while rejecting judgement

A good person isn’t made in here; a good person arrives here, and they either stay good, or they don’t.

Dalton (Leyhill, thirties, mid)

For Nixon and Dalton, secondary parties who denied guilt, life was on hold. Ethical development occurred elsewhere; prison could only make you worse or (at best) impose an ethical stasis. Ethical work in these circumstances consisted in surviving, and resisting taint. In keeping with this preoccupation, both were fluent in their contempt for certain categories of prisoner:

It’s draining being around all these fucking nonces15 […] having these fucking dirty bastards staring at you […] They’re ready to go and put a note in the box, or say something: [contemptuously, in a wheedling tone] “His music was a bit too loud. He didn’t say hello to me.”

Dalton (Leyhill, thirties, mid)

An instructive contrast was evident with the other four in this group, who admitted guilt. They took a more sanguine view of moral status, while also preserving the view that prison was not a place for ‘real’ ethical life:

We’re all just people. We’re all in prison […] No one’s better than anyone else […] I mean, some… I know some people have done worse things than others, I get that. But… I’m not here […] [to take] on board all everyone’s done and all that […] I’m not interested. They’re not my family, they’re not even my… I mean… like… They’re not even real friends, they’re just friends because I’m here.

Liam (Swaleside, forties, mid)

These men wore the ‘murder’ label pragmatically, feeling responsible for the offence but rejecting outside judgement by people who did not understand its circumstances. Such moral fault as they diagnosed in themselves centred less on the offence and more in the lifestyles which culminated in it. These men were not eager to perform the identity of ‘reformed characters’; but they were strongly responsive to the incentive structures of the sentence, complying and engaging pragmatically:

You need to wake up and smell the coffee, innit? I’m doing life, and the chances of me getting out before my tariff is slim to zero, innit? So obviously, I need to do what’s best for me, to progress and go home at the earliest opportunity. So if that means if I need to do seven courses, I’m going to try and get to do these courses, if I need to buckle up on behaviour, I’m going to do whatever I need to do to get to go home to my family, innit? Eyes on the prize, innit? That’s the most important thing.

Leon (Swaleside, forties, mid)

To aim for a ‘prize’ necessitates playing along, even if one would ideally prefer not to be in the game at all. Dalton and Nixon could not do so authentically. Leon, who could, avoided seeing his sentence as an irretrievable loss by ‘gleaning’ (Irwin 1987/1970) from it. He and some others in this group were very interested in education and knowledge, pursued for intrinsic reasons and not mainly because it was expected to lead to employment or work opportunities:

What did you get from doing your degree?

It kind of opened up my eyes a little bit that I had been… let down by society, in that if I had been given the opportunities as a youth, then… my life might have been turned out different. That I actually could have, you know, become something other than what I had become […] Obviously, you don’t really know what you can achieve until you […] set your goals high.

Leon (Swaleside, forties, mid)

4.2.2.4 Summary—money/financial gain murders

No financial gain murder in the present sample was committed alone, and the roles played by participants were important to their ethical meaning. Those who were secondary parties to joint enterprise murders, like those who maintained innocence, found it hardest to think of the sentence as being in any way meaningful. Nixon had constructed a ‘cosmic justice’ narrative; Dalton had not; and both characterised the prison as a parallel, meaningless world: a non-place in which to live non-life while passing non-time (Ievins 2024). Other participants recognised that their offences had been wrong. They struggled to varying degrees with the idea that their intentions (which most characterised as more benign than ‘murder’) no longer mattered after someone had died. They suggested they had lost control, or miscalculated. The defining ethical moment—when it seemed they could have done differently—was often long gone by the time of the offence. They blamed neither the victims nor provocation, instead describing morally compromised circumstances, and outcomes they had not foreseen. Ethical work involved pragmatically taking what one could from the wreckage, while rejecting imposed identities.

4.2.3 Intimate partner murders

Twelve participants (25% of the sample) were in prison for intimate partner murders. Only three cases featured co-defendants, only one of whom was party to the violence (rather than the related charge of ‘assisting an offender’). Nine of their victims were adult women, all either partners or ex-partners; the other three were adult male associates of current or ex-partners. This was, by far, the oldest group at conviction: the median age was forty-one, ranging from sixteen to sixty. Ethnically, eight of the twelve were White; three were Asian; and one declined to describe his ethnicity. They admitted guilt less than other groups, just four (33%) doing so unequivocally, with three (25%) equivocating, three (25%) making strong claims, and two (17%) technical claims of innocence. They had the longest minimum terms of any group, at a median of 19.5 years. Yet all twelve were also serving their first prison sentence. Six had previous convictions, most dating to the 1980s or earlier. Two related to earlier relationship troubles; two were fines imposed in the 1970s for contact sexual offences certain to have been handled more severely today. Accordingly, although they did not think of themselves in this way, some had histories of controlling behaviour and/or violence towards women.

Possessiveness and control showed up less in their accounts of their relationships, and more in their curation of their own narratives. They implicated victims in the offence, and minimised their own responsibility, more consistently than other groups. Sometimes, this was straightforwardly victim-blaming. Others situated the offence in emotional dysfunction, as if the relationship, not the victim, had been to blame for what happened. What was clear, throughout, was that publicly ‘wearing’ the offence was very difficult: there were fewer moral discourses within which claims of provocation would ‘work’.

4.2.3.1 Locating responsibility in intimate partner murders ‘proper’

Without co-defendants, sharing blame around was difficult, and involved a choice: to deny involvement entirely; to blame the victim; or to accept responsibility. Much of how the group reflected on their offences should be understood in this context.

Two participants maintained strong claims of innocence. Like those in every group who made such claims, they went to great lengths in narrating and questioning the case against them (as if to relitigate it). By contrast, questions dealing with moral obligations were answered tersely. There was, simply, nothing to discuss:

Do you perceive any kind of moral judgement or message coming from the conviction?

Never.

Olivier (Swaleside, sixties, very early)

Olivier would be very old by tariff expiry. He saw the post-release period as worthless, and perceived no reason to compromise on his stance, implying that suicide was a preferable choice:

I would have more chance of being dead than alive [by the parole eligibility date]. So no, I’m here by choice [to win my appeal]. I think I would have done myself in without it.

Olivier (Swaleside, sixties, very early)

Ian, who had been in prison for far longer, but also had more potential post-prison years ahead, saw more reason to compromise. This entailed finding past forms of behaviour he did consider morally faulty, and working these around a narrative still premised on the claim of innocence:

[I realised that] even though I was innocent, there are always aspects of your life that you can’t be proud of. For you to then apply for the [offending behaviour] course shows your enthusiasm […] Instead of getting the hump [about participating], you’re making a conscious effort, and I think you get a better response.

Ian (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

Thus Ian, while continuing to deny any responsibility for his ex-partner’s death, admitted past infidelities and parlayed this admission into a reform narrative, addressing the risks officials associated with the murder. Others claimed technical innocence, usually by reference to self-defence:

There was no intent to harm my wife. Never ever. She is aggressive, she stab me once before [when we argued] […] I was scared, I was blackout, I don’t know what happened, it’s just a dream.

Aftab (Swaleside, thirties, early)

Thus even where guilt was admitted unequivocally, narratives of intimate partner murders often questioned blame more subtly. The extract above and others like it usually culminated very long narratives, the effect of which was to present their partners as conniving, manipulative, spiteful, or unfaithful, and thus to implicate them in some way. Finances were particularly commonly presented as a ‘trigger’:

Probation did not understand some offences are “true one-offs”. His wife, a “nymphomaniac”, was constantly having extramarital affairs. Despite these troubles he […] “loved [her] to the end” and “she was only dead because she tried to steal the house” from him.

Emlyn (Leyhill, seventies, post-tariff), from notes

I didn’t go there with any intention to harm a single hair on her head. I went to find out why she took the business from me. And that’s what I wanted to find out. But unfortunately, what happened happened.

Alan (Swaleside, fifties, very early)

In some respects, these exculpatory implications echoed those in the confrontation/fight group. However, as with the financial gain group, there appeared to be few narrative templates available which excused their violence, this time in the domestic context; intimate partner murders, in prison as in wider culture, seemed particularly blameworthy. This might have been the reason the accounts quoted above deflected blame by constructing their victim as a threat to their life, limb, and livelihood. Self-defence, more than provocation, offered moral cover against censure, to the extent that the claim was credible.

Only a few participants in the group threaded this needle by explaining the offence without suggesting that their victims were to blame. They narrated the relationship as a kind of ‘toxic dyad’ which brought out the worst in both parties. What also stood out was the emotional connection these men continued to cultivate with the victim’s memory. In some sense, the relationship lived on:

It’s an offence against her, her family, but also my family, and God […] [Murder] is a massive sin, you know? It’s one of the gravest sins that you can commit in Islam […] If you’ve sinned against an individual, you’ve got to earn their forgiveness. Now, I can’t go up to her and say, “sorry”, but in bettering myself […] all the character flaws I had […] if I improve all of that, then maybe somehow [my wife] will find a way to forgive me.

Rafiq (Swaleside, thirties, early)

Paradoxically, Rafiq felt that he could only expiate his ‘sin’ by obtaining his late wife’s forgiveness. Feelings of this kind perhaps reflected a ‘disenfranchised’ form of grief (Doka 1999): one unlikely to attract recognition, support, or sympathy from others, and thus harder to process. Grant, too, maintained a close relationship with his late wife’s memory. When we started the second interview, he checked the recorder was running and then said he wanted to ‘set the record straight’, having described at length in the first what had become a dysfunctional and very unhappy marriage:

I met Elena16 when I was [age]. Didn’t get married till I was [age]. So that’s [quite a few] years, right? She was lovely. Alright? [voice cracking] And that’s why I still love her today. Alright? I’m not stupid. I wouldn’t have married her if… [pause] Things changed… Alright? So I just want to put the record straight. I’m not saying it was always like it turned out… She was lovely. And that’s… [crying]

I’m sorry… [pause] if I kind of gave the impression I thought something else.

No, no, no, no. It’s just that I thought about it last night and I thought to myself… in talking about how it went wrong… I’ve come across… I don’t want to slag her off, that’s all.

Grant (Leyhill, fifties, late)

Across the intimate partner group, there were three broad stances regarding blame. One (denial) was straightforward. A second (formal guilt with ‘implicatory denial’— see Cohen 1996 p. 522), accepted responsibility but narrated the offence so as to lessen blame. A third stance, moral guilt, accepted responsibility but situated it in a context of tragic (and mutual) dysfunction.

4.2.3.2 Locating responsibility in ‘collateral’ intimate partner murders

It was suggested, in describing the confrontation/fight and money/financial gain groups, that the victim/offender relationship could alter the moral and emotional ramifications of the offence. Contrasting intimate partner murders ‘proper’ with ‘collateral’ offences underlines this point. Compared to those who had killed their partners—especially where those relationships had lasted many years—those with ‘collateral’ offences seemingly encountered less difficulty in explaining their violence, and their accounts could seem glib by comparison. For example, in one case, the claim was that the offence was done in a noble cause:

I killed that guy because I was in love with her. Not out of jealousy [but] to save her […] The best outcome, for all of this—forget me, you know?—is for her to go and flourish and be as good as she can possibly be. That would be, you know, the best outcome. Because then my job is complete, the mission is a success.

Matt (Swaleside, fifties, very early)

Others treated their guilt as a private matter. Having not harmed someone within their family, they were under less pressure to acknowledge harms beyond their immediate circles of concern:

To this day he can’t really understand his motives. He talked about having spent his life solving problems, and how perhaps he saw [the victim] as a problem to be solved […] He hasn’t had “opportunities to discuss it”, and feels the “reaction of men” has been “vindictive and unsympathetic”, while that of God has been “love and forgiveness”. It was “a major thing” to have taken life in this way; and yet he has maintained innocence from the start.

Gerald (Swaleside, seventies, mid), from notes

These instances demonstrate how important are both the ‘depth’ of the relationships ended by the offence, and the cultural ‘templates’ at hand to narrate it.

4.2.3.3 Ethical work—compartmentalising and controlling the narrative

For those convicted of intimate partner murders, ethical work resembled a kind of compartmentalisation. How they saw their offences was well captured by Emlyn’s words (quoted in Section 4.2.3.1): “true one-offs”. The murder was an aberration: something out of character, and discontinuous with the self:

I’ve always been well-behaved, I don’t get into fights, I’ve never been violent except for my crime.

Timothy (Swaleside, twenties, very early), from notes

It followed that they also felt less obligated to become (and to be seen to become) formerly violent men. Indeed, most set little store by ‘reformed’ or ‘rehabilitated’ status as a marker of moral worth. Instead, they emphasised that they were already morally worthy: other prisoners, not them, needed major reformative change:

All the charity work I’ve done on the outside for various people… you know, with regards to [my business], all the things I’ve done to help other people and stuff. And in seeing that, there’s an opportunity here to be a Listener […] Well, that’s something where I can still continue to help people […] [But] so many people are trying to do it for all the wrong reasons.

Alan (Swaleside, fifties, very early)

The sense of themselves as morally worthy people perhaps also explained a marked tendency towards censoriousness (Mathiesen 2012/1965) regarding the prison’s failures to perform its rehabilitative function with those who really needed it:

It’s a nonsense, the whole system. There’s no rehabilitative improvement, really. And above all, it seems to me that self-control is one of the fundamental aims of rehabilitation. Set in a context, a framework of standards… so they recognise the standards and they’re trying to aim for those standards.

Gerald (Swaleside, seventies, mid)

Some members of this group—including Gerald—identified participation in the research with an opportunity to contribute to a conversation about prison reform. They were drawn to prisoner consultation initiatives, and were fluent and assiduous users of the ‘rehabilitative culture’ terminology in vogue with prison managers at the time (see Mann et al. 2018): ‘residents’ not ‘prisoners’, ‘rooms’ not ‘cells’, and so on. Subtly, this signalled their moral alignment with ‘the system’, in contrast with the many other participants who scorned this language.

Only Grant and Rafiq, who admitted moral (not formal) responsibility and saw their offences as culminations, not aberrations, fully accepted that the conviction itself rendered the demand for ethical self-change a legitimate one. They spoke sincerely about change, but this did not mean they accepted wholesale the psychological theories of domestic violence causation promoted by OBPs. Rafiq, in making sense of his offence, preferred a tragic language of distress, remorse, and emotional dysfunction over one of ‘abuse’ and ‘violence’. Nevertheless, he and Grant felt obligated to engage with official terminology, prompting ambivalence:

They will throw those words like “abusive”—that’s a very strong word […] To me […] [it’s] where you’re going out of your way to abuse this person, whether it be physically or verbally. That was never my intention, that was never me. And maybe that’s why I felt bad […] because I did become that person […] “Minimisation”, “justification”, “denial”, “excuse”, “not taking responsibility”, “shifting the blame”. Those are key words that prison psychologists, facilitators use. It’s hard. I can see where they’re coming from, but also not having my side acknowledged, it’s painful.

Rafiq (Swaleside, thirties, early)

The ‘pain’ was that of being defined from outside. Rafiq’s emphasis on his good intentions rhymed with similar protestations across the sample, and were a way of disowning the act. Nonetheless, he admitted having “become that person”, only later discovering a language of emotional dysfunction which helped him explain how. In relinquishing control of the narrative, he and Grant were unusual in the intimate partner group as a whole; they accepted what Rafiq (elsewhere in the interview) called “kind of a new moral compass”. However, his words also suggested feelings of objectification, and a desire for moral recognition, having undergone the painful task of performing ‘narrative labour’ (Warr 2020). Grant, similarly, had demanded recognition in an interaction with a risk assessor, by asserting his ethical worth, and insisting that the assessor reciprocate by taking responsibility for his own faults:

He said that he was a great believer in fate. And he said it wouldn’t have mattered who I married, he believes I would have killed them. Now […] all he knows is what I did. He doesn’t know the background […] So he’s just going on the records. Which I understand he’s got to do. That’s his job, I understand that, I’m not knocking that. But his personal thoughts and his personal beliefs about fate, I think he should have kept to himself […] I said to him […] “the courses that I’ve done […] about changing my beliefs, adapting them, dropping my beliefs completely…” I said, “isn’t it about time you looked at your beliefs?” And he went silent. He just did not know what to say. Because I think he felt that maybe I was right.

Grant (Leyhill, fifties, late)

A few men in the post-tariff stage of the sentence, or who were earlier in the sentence but expected a low quality of life after release, were much less concerned to develop a repentant performance. They questioned what they would gain by admitting responsibility. Demands for accountability were characterised as a kind of assault, not as something which could yield a better selfhood:

I used to feel bad about what happened. And a lot of these [i.e. prison staff, clinicians, providers of treatment], they tried to drive me into depression, almost, over [my offence]. “You must feel bad. You must fucking have remorse […] You’re such a bad person.” They ain’t said that, but it’s kind of that mentality […] They do go, “well, you haven’t got any remorse.” [And I reply,] “I used to have. And you bashed it out of me. I used to care. I don’t give a fuck any more.”

Chris (Swaleside, sixties, post-tariff)

Chris drew attention to something important: that to fully accept blame—to take responsibility without explanation or context and incorporate a wrong into one’s identity—is to be in others’ hands, and to conform to their expectations. To accept blame generated an expectation of reciprocity: that there would be some moral recognition for the major step of doing so. Chris, having been denied parole repeatedly, doubted that this would ever happen.

4.2.3.4 Summary—intimate partner murders

The intimate partner group were more diverse in their backgrounds than those in other groups, and had been convicted older. Their biographies snagged on the offence: in other domains, many had lived highly conventional lives, and most denied earlier involvement in violence or other crime; indeed, their moral attitudes to both were explicitly condemnatory. Prison life, meanwhile, sequestered them away from the kinds of relationships which had produced the index offence, amidst men they saw as far ‘worse’. Against this backdrop, their own violence felt incongruous and unreal, and taking responsibility coherently felt difficult, since it was so discrediting of broader feelings of worth and identity.

The controlling, coercive dynamics said by the Dobashes (2015) to drive intimate partner murders were largely absent from their stories, though my view was undoubtedly impeded by the one-sided accounts I heard. What was striking, instead, in terms of ‘dynamics of control’, was the control many of these men wanted over their stories. Those in the confrontation/fight and money/financial gain groups were more content to be thought of as violent, or as regretfully and formerly violent. The intimate partner group, by contrast, often appeared to be in a kind of denial, characterising their victims (or, less commonly, their relationships) as having been so dysfunctional as to push even a level-headed, conventional, reasonable man over the edge. Their accounts certainly conveyed desperation and overwhelm in domestic conflict, but also often strayed into victim-blaming.

4.2.4 Intensely stigmatised murders

Ten members of the sample (21%) were imprisoned for intensely stigmatised murders. Four had killed adult women, in circumstances recorded officially as involving a sexual motive. Four had attacked elderly people, including five women (whom, in two cases, they also raped) and two men. Finally, two had been convicted of killing infants.17 All charged and tried alone, with no co-defendants, two were of Black ethnicity while the other eight were White. They were the youngest group by average age at conviction, with a median of twenty-five and a range from seventeen to thirty-eight. Nine admitted murder unequivocally, and only one made a (strong) claim of innocence.18 True to the Dobashes’ account, most of these men had been highly marginal: unemployed, and with adverse early experiences common. Seven reported physical or emotional abuse or neglect by one or both parents; five had witnessed violence in the home; four had experienced sexual abuse in the home and elsewhere; five had been taken into local authority care and/or lived in custodial institutions in childhood. Four had no prior convictions and were serving their first prison sentence, but six had served at least one (and four at least two) previous custodial sentences, for offences ranging from theft to (in one case) rape.

The ‘intense stigma’ label is applied here because of the status of their offences in prison and wider culture.19 Nine of the ten admitted guilt unequivocally, and yet four (more than in any other group) declined to describe the offence at all in the interview.20 This, perhaps, hinted at an awareness that what they had done might seem ‘unfathomable’. However, some, mostly those who had confronted the dismal legacy of their childhoods while in long-term therapeutic units, spoke with a qualified positivity about their prison experiences; relief, at having tamed the after-effects of early trauma, was evident. Although this group accepted responsibility more than any other, many perceived that prison authorities tended to view them cautiously, as ‘damaged goods’: stigmatised, vulnerable, dangerous, and neither autonomous nor responsible. This grated with some.

4.2.4.1 Dissociation and responsibility

Though this group readily accepted their guilt, these offences remained difficult to contemplate, and to describe or explain. Accounts of the offence in interviews were often matter-of-fact, emotionally detached, unelaborated, and described with a coldness which nonetheless seemed somehow protective:

I went upstairs […] I opened this room, she was in there, but she was asleep […] So I’ve […] opened the thingy, and she must have heard me […] She was starting to scream. I said, “listen, you don’t have to scream, innit.” So I punched her […] [and then] I raped her. And then I ended up strangling her.

Jeff (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

Dissociation and detachment related to the offence were sometimes described explicitly:

He remembers thinking he was going to [kill] her but felt as if he was outside his body […] [and] “far from myself” […] [He had] no sense at the time that what he was doing was right or wrong and didn’t pause to reflect […] [but] simply “acted on what came into my mind” and “went with the flow”. He didn’t feel angry with her, but distant, cold, and detached. It was only when police later questioned him that it sank in: it was “impossible to explain”.

Derek (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff), from notes

The words at the end of this extract, a direct quote, are highly significant. Actions that are “impossible to explain” are also deeply isolating. Like all stigma (Goffman 2022/1963), they discredit the subject. When these men described the early sentence stages, they often referred to extended periods of self-seclusion, in which the impossibility of accounting for the offence cut them off from the world:

It was, “oh fuck, oh fuck, what have I done”, sort of thing. I was in complete denial, complete and utter denial […] I was in denial for, what, three years? Just point blank, “nah, it weren’t me” […] Looking back now it’s mainly because I was so deeply ashamed of what I did.

Adam (Swaleside, twenties, mid)

Social exile was often reinforced by condemnation from others; fear of other prisoners was often evident, and was a cause of self-seclusion for some:

[HMP X] was “a living nightmare”: he received beatings from officers and other prisoners. Members of his family sold stories about him to the press, then cut him off.

Derek (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff), from notes

[I transferred to another prison] but there is no video camera [on the wings] there, so basically within two days I was behind my door with people threatening my life […] and I spent half a year behind my door with no access to really anything. There were times when for ten days I could not get out for shower and phone calls or anything.

Janusz (Swaleside, thirties, mid)

In most cases, then, dissociation or denial had been the public stance, but these men felt deep shame in private, of a kind which felt impossible to reckon with because it was so hard to offer an account which was both truthful and morally coherent.

4.2.4.2 Ethical work—finding explanations

Coming to terms with the offence entailed finding ways to turn private shame into public responsibility. It did not necessarily neutralise or deflect internal feelings of shame centred on the offence:

It’s pretty brutal. I mean, I still get upset about it, but I’ve managed to sort of… Not forgive myself, exactly, but move on, to be practical and pragmatic about where I was then, and where I am now. Yeah. But it’s something I’ll have to live with for the rest of my life […] I deserve to be in prison.

Daniel (Leyhill, fifties, late)

The impossibility of explanation was most evident when participants preferred not to describe the crime at all. They could (and did) revisit factors which had played a part, including violent and sexual victimisation, substance misuse, or mental illness. But they stopped short at the offence itself. Jeremiah, who had previously been accustomed to violence among his (male) peers, said that nothing had prepared him for the psychological impact of murdering a woman in her home using extreme forms of violence which had greatly aggravated his sentence:

Before, there were times when I felt really angry, that I felt like, yeah, I could actually have hurt someone… But like… the person that I killed… you know, the way… you know… I killed them… and stuff like that… Like, I didn’t think that… you know, you know… that would have happened as well […] I felt like, you know… Just like… I kind of lost myself […] Or maybe like, I felt like, you know, I lost part of myself […] after I committed that crime.

Jeremiah (Leyhill, thirties, post-tariff)

The notion of ‘losing part of oneself’ captures the sense of psychological and personal disintegration caused by trying to incorporate an intensely stigmatised act into one’s story. Yet, to not do so risked allowing self-seclusion to congeal into permanent exile. Most of these men, eventually, recognised what Nicholas expressed most clearly: that there was a frontier, beyond which dissociation became fantasy, and withdrawal became detachment from reality:

At that beginning stage it was easier [to] place myself in a chain of thoughts […] where what had happened never really happened […] eventually it [got] to an extent where you find yourself too far gone […] I was living in the past, okay? And living outside [the prison], but it was not the life that I had lived […] I was kind of re-living my life but with… you know, making up a different kind of history for it.

Nicholas (Leyhill, thirties, post-tariff)

What made explanation difficult for men in this position was not that they had killed someone, but rather a combination of who they had killed, and the cruelty or indecency legible from the how and the why. This was most evident with offences recorded as involving a sexual motive, which, more even than the killing, could seem the unfathomable detail. Only three of the six participants with offences of this kind readily admitted the sexual element, and one other had changed his stance:

I denied the rape. To me, to me… All right, taking somebody’s life is bad, yeah. But, but… raping an old lady, to me, it’s not acceptable. And I thought that… that was… that was worse. So I denied that for years, and I just said, “I admit the murder”.

Jeff (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

Owning up to a sexual motive was extremely difficult, both for internal and external reasons. Even in treatment settings, such disclosures could bring lasting repercussions:

Ever since I have done that [i.e. disclosed], there are […] prisoners who are aware of it and it’s been passed on year by year to different establishments […] it rebounds in the prison wherever you go and then it follows you through word of mouth […] [People think:] “that guy has got no standards and no morals, he’ll do whatever he wants” […] You can start believing that you’re a bad person from what they say. It can taint your thoughts and ruin your mental state.

Derek (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

Derek’s words recall the finding that highly stigmatised offences ‘stain’ those responsible with a sticky, persistent taint (Ievins 2023). ‘Stained’ people are impugned with not moral but ontological deficiency;21 the conviction “sets [them] apart, pollutes [them]”, feels “impossible to escape”, and is “indelible and communicative” (Ievins 2023 p. 43ff). Offences in the confrontation and financial gain groups were often more ‘serious’ by the crude metric of tariff length, but intense stigma was its own burden.

A couple of men, however, both with experiences of long-term therapeutic intervention, accounted for the offence more fluently and with fewer signs of continuing dissociation. Therapy, it seemed, had bridged the gap between early trauma and subsequent violence. In telling their stories, they seemed less preoccupied by how others perceived them:

Have there been people during your sentence you have looked up to or admired?

[24-second pause] No. Not in prison, no. I have sat there and thought, “Oh, I wish I was like you.” I used to do that a lot […] But then after […] therapy it was all about me. It was all about accepting me for who I was, and it was about that journey being my journey, not other people’s journeys. So—although this sounds a little bit selfish—it was about me from that point onwards.

Nicholas (Leyhill, thirties, post-tariff)

Nicholas’s suggestion—that self-possession might be perceived as “selfish”—was significant, drawing attention to limits on where these more fluent offence narratives could go. Therapy, to be sure, relieved some kinds of pain, and these men certainly found relief from shame in this. It could not, however, enact a deeper form of moral repair, something Harry regretted:

[I] found out [through an] impact statement the perceptions of the [victim’s] family… that they perceived me as someone who’s not taken responsibility […] That troubled me greatly because whilst I can appreciate their grief it seems to me that that letter that I wrote, […] in fact it [must have] never reached the family. Because part of that letter was to impart to them how much sorrow and regret I have, how much how much pain I’m experiencing, because—that’s selfish—but I didn’t […] want them to think I didn’t have any remorse […] I feel sad […] for them because I didn’t want them to think I’ve wasted my time in custody.

Harry (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

Having come to terms with shame, men who authentically took responsibility for intensely stigmatised murders wanted to assert a kind of dignity. Others, in preferring to keep them safely ostracised, continued to deny them this:

You get moral judgements all the time, even from cons every day. They’re all, “nonces this,” and, “nonces that,” and “nonces this.” And I think, “You’ve still got trouble in your soul. You’ve not come to terms with who you are, what you’re doing. You’re blaming everybody else. Just get on with your own shit.” […]

[…] Are you open with people you associate with about what you’re in for?

Yes. A lot of people don’t like that, either […] They resent your inner strength, for some reason.

Fred (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

Thus far, we have seen that men with intensely stigmatised offences felt shame, and found it difficult to account for the full gravity of their actions. Those who had experienced intensive long-term intervention fared best in this respect.

4.2.4.3 Explanation, progression, and ‘ethical loneliness’

The situation described above was a double-bind: those who ‘went deep’ in explaining their offences arrived at answers nobody wanted to hear. Therapeutic discourse could appear to shift them from one form of isolation into another: from dissociated seclusion, into what (they worried) might seem an inappropriate self-absorption, or even solipsism.

As a whole, the intensely stigmatised group skewed heavily towards the later and post-tariff sentence stages.22 Many were disappointed or disillusioned, because after repeated parole knockbacks they perceived that taking responsibility had yielded them no reward:

Surely, they can see when enough is enough? […] I vent a lot because I’m very frustrated […] I’m ready to go. I want to get on and live my life and settle down. Maybe meet somebody, make some new friends. Re-establish ties with my family and do the things I like to do.

Fred (Leyhill, fifties, post-tariff)

If I had my parole and they said, “We would like you to do another course”, I will tell whoever it is on the parole board they can shove it up their fucking arse. That is it. They have had me for [over twenty years]. I have done everything they wanted me to do and more. If they want me to do more courses to prove it to them, then they can all fuck off, they can all jump off a cliff.

Tom (Swaleside, fifties, post-tariff)

Fred and Tom questioned, in effect, the implicit dialectic underpinning retribution, with its emphasis on responsibility: that there will be a two-way moral dialogue; that penance or repentance or self-reform is appropriate; and that punishment will one day end (see, e.g., Bottoms 2019; Murphy 2011; Tasioulas 2006, 2007). Instead, what they found at the end of this road was further indeterminacy, hemmed by the unpredictable demands of ‘soft power’. This was ‘ethical loneliness’,23 because it showed signs of having lost “trust in the world”. Gone was

…the certainty that by reason of written or unwritten social contracts the other person will spare me—or, more precisely stated, that he will respect my physical, and with it also my metaphysical, being.

Jean Améry (1964), quoted in Stauffer (2015 p. 16)

The closing summary of this section unpacks this idea further.

4.2.4.4 Summary—intensely stigmatised murders

The philosopher J.L. Austin’s seminal treatment of excuses has inspired several strands in the anthropology of ethics (e.g. Das 2012; Keane 2014; Sidnell 2010). Austin’s insight was that, in ordinary language, the giving of excuses is central to the construction of responsibility:

I do not exactly evade responsibility when I plead clumsiness or tactlessness, nor, often, when I plead that I only did it unwillingly or reluctantly, and still less if I plead that I had in the circumstances no choice: here I was constrained and have an excuse (or justification), yet may accept responsibility.

Austin (1956 p. 7)