This is the second of three posts in a series looking at rehabilitation as an aim of punishment. You can find the first post in the series here.

Arguing for an end to rehabilitation

As a consequence of the arguments I summarised in the first post in this series, the AFSC report’s authors argued for a range of reforms which deliberately excluded rehabilitation as an aim of punishment. One example that they demanded was an end to indeterminate sentences. Although today (in England and Wales, at least, and with the significant exception of the much-criticised IPP sentence) these are used only for more serious offences. However, they were relatively common in post-war America. Rather than being imprisoned for set period of time, many prisoners were detained at the discretion of prison officials, who possessed the power to judge whether they were ‘reformed’ (and therefore eligible for parole) or not.

The kinds of experience this provoked can be seen in a famous scene from the film The Shawshank Redemption.

I like how this clip captures the powerlessness and disillusionment felt by prisoners who could come before parole boards again and again without knowing the standards by which they were being judged.

The ‘crime of treatment’

According to Struggle for Justice, parole boards and other prison officials wielded excessive and corruptible discretionary power, which was liable to become illegitimate. They described this as a ‘crime of treatment’, in which policies with ostensibly rehabilitative aims (such as the offer of parole) were in fact principally used as an incentive to secure control within prisons. They therefore served the interests of prison staff, not of prisoners who they were intended to benefit. Moreover, the report argued, this was done in a discriminatory way: it systematically disadvantaged prisoners (often non-white, uneducated and poor) who prison officials (often white, educated and middle-class) were more likely to regard as ‘dangerous’.

This was done in a way which systematically disadvantaged prisoners (often non-white, uneducated and poor) who prison officials (often white, educated and middle-class) were more likely to regard as ‘dangerous’.

Limits to rehabilitative knowledge

Rehabilitative punishment has a contradiction at its heart: it’s extremely difficult to predict with perfect certainty how another human being will act, whether they have ‘changed’, or whether they are ‘dangerous’. People are different in different contexts, and might respond in different ways if presented with different sets of provocations; to some degree, practices like parole and ‘furloughs’ (temporary releases) were originally intended to permit such changes of circumstance to be monitored and managed in controlled conditions.

Even so, the kind of knowledge and reciprocal trust which might give us reasonable confidence in some people some of the time, cannot easily be obtained through surveillance and coercion. For authors of Struggle for Justice, they were so difficult to achieve, and so vulnerable to corruption under the imbalances of power present in prisons, that they tended to come down not to fine, contextual judgment and ‘deep knowledge’ of prisoners by staff; but instead were over-reliant on crude and imperfect (but observable) indicators of change, such as reconviction rates. These, however, were highly problematic means of approaching the question of whether to trust someone enough to release them:

We have no way of determining the real rate of recidivism because most criminals are undetected and most suspected criminals do not end up being convicted. Recidivism rates are also subject to […] unconscious bias […] introduced by the tendency of predictive and diagnostic judgments to become self-fulfilling prophecies. For example, those release on parole from a treatment program are likely to be formally or informally classified for the purpose of parole supervision into good risks (responded favorably to treatment) and poor risks (resisted treatment). The [latter] are likely to be subjected to tighter surveillance; their violations are therefore much more likely to be detected; their parole is more likely to be revoked; and the resulting differences in recidivism rates emerge as a “research finding” validating the efficacy of the particular treatment program. Struggle for Justice, pp.42-3

In the face of such difficulties, it appeared to the authors of Struggle for Justice that punishment should be very strictly limited in scope and in ambition, giving up its claim over the prisoner’s subjectivity, and instead opting for a more limited (but controllable) conception of the aims of punishment:

[T]he whole person is not the concern of the law. Whenever the law considers the whole person it is more likely that it considers [irrelevant] factors [which relate instead to] influence, power, wealth and class [and not] the needs […] of the defendant […] Focusing on the criminal rather than the crime tends to [neglect] the more tenable view that criminal acts are committed by a very large number of persons […] spread throughout all sectors of society. >

Struggle for Justice, pp.147-8

Abolition or reform?

Struggle for Justice also considered the perennial question of penal abolition. While convinced that it would be better to ‘tear down’ all jails than to ‘perpetuate the inhumanity and horror being carried on in society’s name behind prison walls’ (p.23), the authors were not convinced by the argument for prison abolition, a scepticism which may have followed from their belief that rehabilitative aims had only served to disguise the true nature of punishment. Prison abolition, they said, would simply result in the need to replace prisons with some other form of coercive institution, and thus constitute ‘label switching’:

[C]all them “community treatment centers” or what you will, if human beings are involuntarily confined in them they are prisons.

Struggle for Justice (p.23)

Their answer was to limit the aims and scope of punishment. Inducing people to change through the use of coercive power had no legitimate place in punishment, though every effort should be made to offer help on a voluntary basis to those who wanted it.

Retribution alone

Instead, Struggle for Justice argues that punishment should be framed solely by retributive aims. Here the report’s authors were espousing what became known as ‘truth in sentencing’.

The law should specify a set of clearly-stated punishments, specified for all crimes. Where a crime was serious enough to mean imprisonment, sentences were to be determinate (i.e. of a fixed length). Penalties should be backwards not forwards-looking, in other words. They should apply identically to all people convicted of a given crime, and should be used only when all of the following conditions apply (pp. 149-153):

- there is a ‘compelling social need to compel compliance’ (i.e. others’ rights or safety are threatened by a given person’s conduct, rather than their moral views offended by it);

- there is no feasible but less costly way to obtain compliance;

- punishment is expected to produce a greater benefit for society than simply doing nothing;

- other courses of action have been exhausted;

- punishment is no more severe than necessary;

- punishment must fit the crime (rather than having ambitions to ‘treat’ the person).

Meanwhile, the aim of making people ‘better’ should be organised on different lines, and freed of coercion:

We recommend that a full range of therapy, counseling, and psychiatric and educational services be made avaialable, free, on a voluntary basis, to the entire population, inside prisons and on the street.

Struggle for Justice, p.171

The AFSC’s was not the only call for the reform of rehabilitative punishment in the 1970s. Like many reforms, these calls melded with other agendas, combining with unforeseen consequences which reformers would not have wished for. This is a fascinating and tragic cautionary tale, but it has been well told elsewhere.

In a final post in this series, I will think about how relevant the findings of Struggle for Justice are in the UK today.

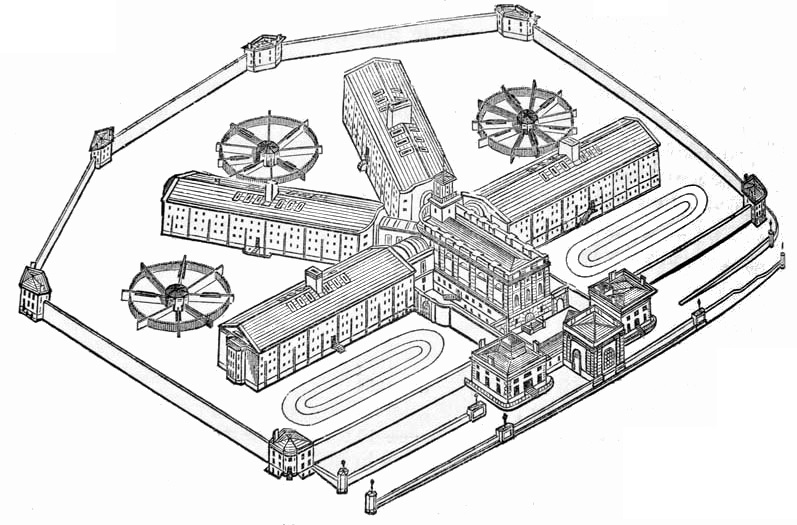

Image in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Reuse

Citation

@online{jarman2019,

author = {{Ben Jarman} and Jarman, Ben},

title = {Rehabilitation and the Aims of Prisons (Part 2)},

date = {2019-02-04},

url = {https://benjarman.uk/changing-inside/rehabilitation-aims-prisons-2.html},

langid = {en-GB}

}